At the Michigan State University Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory, highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) has been a priority since this strain was detected in Michigan poultry in early 2022. As the only laboratory in Michigan approved by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) to test for HPAI in any species, MSU’s Laboratory is a member of the National Animal Health Laboratory Network, a network serving as the first line of testing for high-consequence animal disease outbreaks.

It’s unusual for an outbreak to last more than two years, but this strain of H5N1 HPAI has proven to be just that: highly unusual. The Laboratory team has had to respond to many new challenges.

In short: Because the virus has been detected year-round instead of seasonally, and emerged in unexpected species.

Avian influenza viruses constantly circulate in wild bird populations and are classified as either highly or low pathogenic depending on how they affect domestic poultry. Usually, infected wild birds are asymptomatic. This strain, however, has caused widespread illness and death in wild bird species, notably birds of prey and scavengers.

Just months into the US outbreak, the virus was detected in several species of wild mammals, mainly scavengers presumably eating infected carcasses. While some mammals are susceptible to avian influenza, the scope and severity of the disease was surprising. This strain continues to spread globally, and infections have spread to more species—even marine mammals.

It is typical for HPAI infections in domestic poultry to occur during seasonal wild bird migrations: appearing in winter, continuing through spring, and re-emerging in fall. But after two years of this pattern, something happened in March of 2024 that no one saw coming—HPAI was detected in sick Texas dairy cattle. Days later, the virus was detected in Michigan cattle, followed shortly by detection in a Michigan commercial poultry facility. Six more commercial poultry detections followed. As of late August 2024, nearly 7 million domestic birds have been affected in 10 commercial and 26 backyard flocks in Michigan, and more than 100 million domestic birds in more than 1,000 flocks nationwide since 2022.

Dairy cattle were exposed to the B3.13 genotype of the H5N1 virus by a single transmission event from wild birds, with subsequent transmission within and across herds. The virus genotype associated with clinical disease in cattle is very similar to other H5N1 genotypes and causes severe illness and death in domestic poultry. Subsequent testing and sequence analysis indicates that the commercial poultry facilities in Michigan and other states were infected by the same B3.13 genotype circulating in local cattle. On August 26, the Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development announced the 28th affected dairy herd in the state. Collective efforts to prevent spread of the virus from cattle to other susceptible species are critical not only to protect the health of those animals, but also to limit the virus’ chances to mutate and become more adapted to mammals including humans.

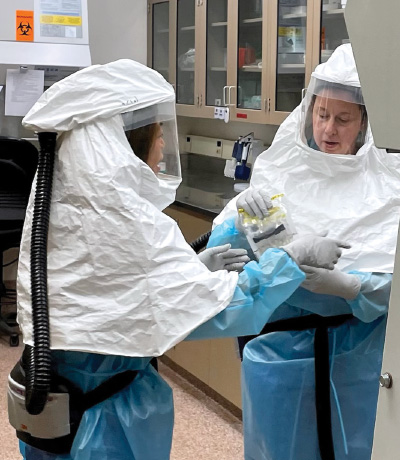

Responding to the increased demand and requirements for testing at the MSU VDL was a team effort. The Laboratory needed to be able to test for HPAI to support disease detection, permitted movement of animals and products, surveillance, and research to learn more about how the virus is affecting cattle. HPAI suspect samples are handled in the Laboratory’s biosafety level-3 laboratory, which requires additional biosafety and biocontainment measures—wearing personal protective equipment such as Tyvek overalls and powered air purifying respirators, for example.

Those trained and authorized to perform the testing felt the increased workload most acutely.

“We’ve been performing HPAI testing daily since late March 2024,” says Danielle Thompson, lab manager of the Virology Section.

“For several weeks following detections in commercial poultry facilities, we were testing seven days a week so producers could continue to operate. We never know how many samples we’re going to need to test each day, and that makes it hard to plan. We still have other testing to do, so we have been juggling a lot over the past several months.”

But testing was just part of the workload. Operational planning required tremendous effort.

“We created, and re-created processes and documents as the situation evolved. We implemented a curbside sample drop-off process so that those delivering samples never enter the building. Going outside for samples disrupts our regular workflow, but good biosecurity and biocontainment requires limiting access to the facility,” explains Dave Korcal, associate director and quality manager.

“The USDA has critical and detailed requirements for reporting results. This team has gone the extra mile to make sure all cases are entered into the system correctly and results are transmitted without errors.”

Dr. Kimberly Dodd, dean of the MSU College of Veterinary Medicine and former director of the Laboratory, has led the Laboratory’s HPAI efforts.

“I am incredibly proud of the entire team,” says Dodd. “The workload has been demanding, with new challenges requiring new solutions, and the team has taken everything in stride— even when that meant working late or on weekends,” says Dodd.

“Over the past several months, Laboratory faculty and staff demonstrated they have the knowledge and skill to safely respond to an outbreak. They’ve also shown their commitment to protecting animal and public health here in Michigan and beyond.”