Nearly four decades after the nuclear disaster in Chornobyl, the region remains one of the most radioactively contaminated areas on Earth. Yet, within this hazardous landscape, wildlife thrives. Forests, wetlands, and overgrown abandoned towns have become home to diverse species—from beavers and moose to wolves and rare brown bears.

For scientists, the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone (CEZ) offers a one-of-a-kind natural laboratory to study how radiation exposure affects life. And while much research has focused on large mammals and birds, one team is turning its attention to a much smaller resident: ticks.

Dr. Artem Rogovsky, associate professor of Pathobiology and Diagnostic Investigation at the MSU College of Veterinary Medicine, studies tick-borne diseases and clinical veterinary microbiology. His research primarily focuses on Lyme disease, caused by the tick-borne bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi.

Rogovsky’s recent work includes developing a rapid diagnostic test for Lyme disease using Raman spectroscopy and identifying a murine model of Lyme neuroborreliosis. Now, with the work of doctoral student Natenal Neumann, a long-simmering project on the microbiomes of ticks living near Chornobyl is also advancing.

The inspiration for the study began during Rogovsky’s doctoral studies when he became fascinated with the impact of environmental radiation on microbial communities.

“I had this idea to go to Chornobyl and see how long-term irradiation influenced the microbiota of ticks,” recalls Rogovsky, who is originally from Ukraine.“I was interested in how extreme environments shape microbial life.”

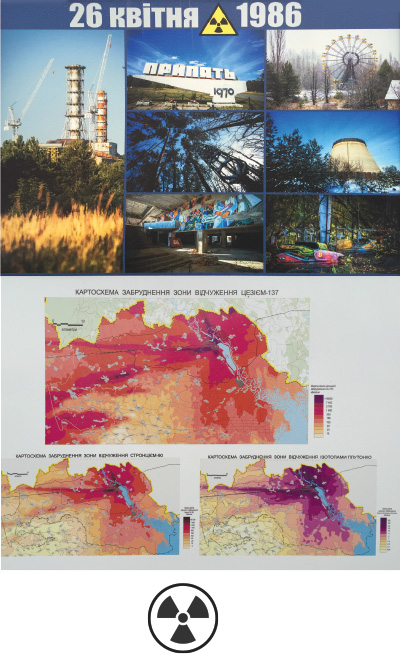

Rogovsky spent a couple of years finding the right collaborators, securing funding, and wrangling permits to collect ticks in the highly restricted 10-kilometer and 30-kilometer zones surrounding the reactor. Finally, he traveled to Chornobyl in 2016—coinciding with the 30th anniversary of the nuclear meltdown.

“There I was in Chornobyl,” he says. “We picked up a lot of ticks.”

His team collected Ixodes ricinus and Dermacentor reticulatus, a common hard tick species in Europe and vector of tick-borne pathogens. They also gathered control samples from four non-contaminated regions, including Kyiv.

For the last two years, Rogovsky’s Ph.D. student, Nate Neumann, has been leading the data analysis, comparing the microbiomes of ticks from Chornobyl with those from control regions.

Neumann recently presented his findings at Michigan State University’s One Health Day, where he won first place for his scientific poster presentation. The research sheds new light on how prolonged radiation exposure could have shaped the microbial communities within these tiny arthropods—raising questions about the broader ecological consequences.

Using high-throughput DNA sequencing and bioinformatics, Neumann analyzed the microbiomes of 160 ticks from Chornobyl and 277 from control regions. His study identified several bacterial genera as distinct microbiome markers of radiation-exposed ticks.

“Basically, we found bacteria that are only present, or significantly associated, with ticks from Chornobyl,” says Rogovsky. “We now have identified some markers of irradiated ticks.”

These findings give us a glimpse into how microbial life adapts to conditions of extreme and prolonged radiation