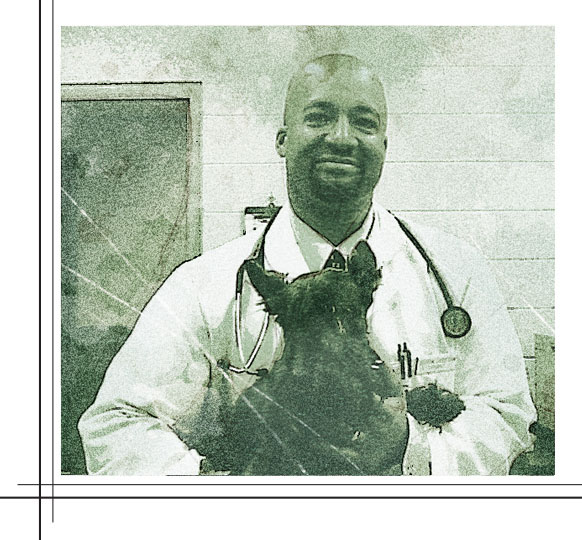

Third Time’s the Charm: from Aspiring MD to DVM and PhD

By Katheryn L. Sullivan Kutil

By Katheryn L. Sullivan Kutil

For many, becoming a veterinarian is a childhood dream; for Dr. Stephan Carey, associate professor at the Michigan State University College of Veterinary Medicine, that wasn’t the case. “I went to Duke University for undergrad and studied human medicine. I had way too much fun, but I also had a falling out with human medicine. Let’s just say, timing is everything,” says Carey.

During his senior year, Carey’s undergraduate advisor suggested veterinary medicine. “It was a great suggestion, one that changed the course of my life—well that, and the time I spent in a toxicology and research laboratory for the Environmental Protection Agency while I completed my prerequisites for vet school.” Carey envisioned himself working in a small animal hospital. But that vision changed when he was encouraged by his vet school mentors to consider specialization. “That’s when I landed at MSU for my rotating internship,” Carey adds.

That was in 2000, and he’s been a Spartan ever since. “I fell in love with MSU, and I fell in love with respiratory disease and physiology.” Carey decided to complete an internal medicine residency. “I realized once I got here that there were all these respiratory-disease powerhouses: Ed Robinson, Fred Dersken, Sue Holcombe—and they were all in large animal. Lucky for me, Dr. Ed Robinson became my de-facto mentor, and he introduced me to the one-and-only, Jack Harkema.”

Carey’s work with Robinson and Harkema originally was set to be a three-year residency project, after which he would begin his career as an internist. But again, Carey’s mentors and his own passions led him in a different direction. “The fact that Dr. Harkema was a veterinary pathologist who was impacting human health, creating advocacy to reduce air pollution, and protecting human and animal health—I was hooked. So, Jack convinced me to stick around and get my PhD.”

Industry stakeholders supported Carey’s decision; Pfizer Animal Health (now Zoetis) sponsored. “Suddenly, I was given this opportunity to combine my new-found love for teaching with research and clinical training. It was truly perfect timing. Not to mention, I absolutely loved the work. I just couldn’t say no.”

Fast-forward 22 years, Carey is a leading toxicology researcher, clinician, and educator. “I had no idea that I was going to end up where I am now. I never envisioned that this is what my career would look like, and I really owe that to the product of fortunate timing, wonderful mentors, and opportunities at every step along the way. Now that I’m here, I couldn’t see myself anywhere else.”

Carey finds the multitude of opportunities to teach veterinary medicine to be his greatest reward. “When I’m giving a course on continuing education and I hear practicing veterinary professionals say, ‘I wish I had you in vet school’ or ‘I wish you had been the person to teach me about immunology or respiratory vaccinations,’ that’s the most flattering and rewarding thing to me.”

“That’s one of the things I like to bring to teaching: to make sure I know the material well enough to be able to teach it in multiple ways,” Carey continues. “If someone doesn’t get it, I need another way to come at it. That’s one of the most-valuable lessons I learned from several of my mentors—Drs. Robinson, Ewart, Holcombe, and Harkema.”

Carey is a star educator, but his research is nothing to gloss over. “I love the fact that one week, I can be impacting children with cystic fibrosis and the way they receive therapy, and the very next week, I can be impacting cats that have respiratory diseases or dogs that have infectious diseases.”

From teaching students and treating patients, to advancing human and animal health through research, Carey is among the best of the best. “When I started vet school, I had it in my head where I was going; where I landed is so, so much better,” says Carey.

By Allison Hammerly

For many, graduation from professional school is one of life’s biggest milestones. It triggers a cascade of enormous changes in a person’s career and personal life.

Dr. Erica Ward embraced that change. Just days after her 2013 graduation from MSU’s College of Veterinary Medicine DVM Program, she moved from the United States to Thailand, a country she already considered her second home, thanks to several months of externships and volunteering during school breaks.

That experience helped Ward secure a job as a veterinarian at an elephant sanctuary outside of Chiang Mai, the same one she had worked with during veterinary school.

“While at the sanctuary, I worked with an extremely talented and inspirational elephant trainer, Chrissy Pratt, who now has her own non-profit, Elephation,” Ward says. “She taught me so much about elephant behavior and how to make elephant care less stressful by giving them the opportunity to voluntarily participate in medical care through positive reinforcement in protected contact.”

Ward developed a passion for teaching and mentorship, especially in promoting animal welfare and conservation. In 2016, her interests led her to a position at Loop Abroad, a veterinary-based study abroad company. In her current roles as academic director and head veterinarian, she helps develop and expand study abroad programs in Thailand and around the world.

“I have seen how our programs expand the worldview of younger generations and inspire them to care about conserving nature,” she says. “While students volunteer, they support organizations that help animals, whether through spay/neuter campaigns, wildlife rehabilitation and release, or improving welfare for captive wildlife. When students return home, they share what they learned with others.”

The initial spark that led Ward to work with elephants was given space and resources to grow, thanks to her peers at MSU.

“I wouldn’t have even had the opportunity to work professionally with elephants if it wasn’t for many of my classmates who generously traded clinical course rotation blocks with me so that I could arrange my schedule to spend three months of my clinical year in Thailand,” she says.

While abroad during her clinical year of veterinary school, Ward completed externships and continued her work at Chiang Mai University and Elephant Nature Park. These experiences pushed her to pursue a career in elephant medicine.

“Several MSU clinicians, including Dr. George Bohart and Dr. Lori Bidwell, took extra time helping me extrapolate what we were learning with domestic animals in developed countries to elephant medicine in underdeveloped countries,” she says. “I was inspired by how passionate my instructors were about the classes they taught, which encouraged me to find my own passion. Once I found my passion, I felt surrounded by encouragement and support. After moving to Thailand, I occasionally reached out to MSU instructors, like Dr. Eric Schroeder and Dr. Laura Nelson, with questions about the cases I was treating.”

To aspiring veterinarians, Ward offers bracing words of advice.

“Keep your options open and don’t be afraid to pursue a dream or try something new, no matter how crazy it may seem,” she says. “Try to have empathy for everyone, even those who treat you poorly. Having this mindset will give you a better outlook and make you a better teammate. Be kind and helpful.”

By Emily Lenhard

Some of the oldest stories in existence are written on ancient animal skin, but Dr. Ian Moore’s modern tales use tissues from the body in a different way.

At the National Institutes of Health, Moore examines slides of miniscule tissue samples from animal models for signs of disease. He creates hundreds of slides from a single quarter-inch sample, and each slide has the potential to tell him something different.

“Every slide is like a new page of a book. You see another part of the story,” says Moore. “You section the tissue thin and it’s like pages in the story that tell you where the virus was and which cells it was infecting.”

As a general pathologist, Moore’s work focuses on a wide range of tissues from all throughout the body; his norovirus research is focused on the gastrointestinal system, and his COVID-19 work focuses on lung tissue. But regardless of tissue type, Moore is focused on telling the whole story.

“You want to reproduce what you would see in a person if they were infected with that disease. If it doesn’t cause the same clinical disease in the animal model, there’s a break in the story; you’re missing pages,” says Moore.

One of Moore’s recent publications hones in on which cells are infected by human norovirus, a highly contagious viral agent that causes vomiting and diarrhea in people; it can be life-threatening, especially for immunocompromised individuals.

This discovery means Moore and his collaborators are one step closer to finishing this chapter of norovirus’ story.

“If you know the cells a virus targets and how it works in causing disease, then you can start making a plan for targeted vaccines, other preventatives, and improved therapeutics,” says Moore.

Expert scientists and storytellers aren’t just born; they’re shaped by those who lead them. As a PhD candidate and pathology resident at MSU from 2006 to 2009, Moore had no shortage of strong mentors. He studied in the College of Veterinary Medicine’s Department of Pathobiology and Diagnostic Investigation, and completed a residency at the MSU Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory. Moore says Dr. Kurt Williams, Dr. Dalen Agnew, and Dr. Tom Mullaney each were critical in helping him become the pathologist he is today.

“Teaching and encouraging are different things. I can tell you something, but if I encourage you to use it, pursue it, you become deeper in it. And because you’re interested, I go deeper, and because I’m interested, you go deeper,” says Moore.

“The pathologists I trained under who really made me—those people encourage you. That’s why I’m doing what I’m doing now, and I’m trying to give the same thing back to students. It’s funny to look back and try to think about how people shape you. It’s really apparent in my case.”

Moore says his path hasn’t been easy, but it’s doable and worthwhile for those who put in the work.

“If it were easy, everybody would do it. You have to see something at the end of the road that really makes you want to go through it. As long as you have the right motivation, you can move through it. And if you haven’t had that moment of doubt, you’re not doing it hard enough.”

By Courtney Chapin

At the Michigan State University Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory, the Necropsy Service performs postmortem examinations on a wide variety of animal species. Necropsies provide food animal producers, zoos, state and federal agencies, and pet owners with important information regarding factors that contributed to an animal’s death. This kind of work might not be the first thing that comes to mind when thinking about veterinary medicine. But for Janet Hengesbach, an alumna of MSU’s Veterinary Nursing Program and Necropsy Service supervisor at the Laboratory, it’s been her daily routine for 15 years.

Hengesbach grew up on a dairy farm, where she helped take care of her family’s cows, horses, dogs, cats, and rabbits. Beginning in elementary school, she was active in 4-H and enjoyed hunting a variety of wild animals. “I always wanted to help the veterinarian in any way I could while they were treating our animals,” Hengesbach remembers. “I liked to feel as if I had a part in helping them get well. I knew that veterinary medicine would be something I would be passionate about as a career.”

While enrolled in the Veterinary Nursing Program, Hengesbach took the necropsy rotation elective at the MSU Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory, and greatly enjoyed the Service’s environment and purpose. At the time, she thought it would be something she would enjoy as a career. After college, she took a veterinary nursing job dealing with large animal emergencies at the MSU Veterinary Medical Center. But when a position opened in the Laboratory’s Necropsy Service, she jumped at the opportunity.

“The education and hands-on training through the Veterinary Nursing Program allowed me to hit the ground running and excel in my job. The knowledge I gained in medical terminology, venipuncture, anatomy, and overall organ systems was especially useful,” says Hengesbach.

Part of her job involves teaching and training the Veterinary Medicine and Veterinary Nursing students how to perform a necropsy properly and safely. “I enjoy when the lightbulb comes on and the students say, ‘That’s what we’ve been reading in the textbook. This makes so much sense now!’” Hengesbach explains.

For many people, working with deceased animals might be a hard thing to do. But Hengesbach says she really enjoys playing a role in finding answers for the Necropsy Service’s clients.

“The clients who have large animals may have a herd problem going on that is causing multiple animal losses. These animals are the farmer’s lifeline. If the animals do well, the farmer does well. There are several diseases that can spread through a herd if the correct treatment is not given,” explains Hengesbach. “I also like trying to find closure for our small animal clients to help them understand why their beloved animal has passed away. I feel there is great purpose to the service we provide, and I take great pride in knowing I am a part of it.”

By Esther Haviland

Dr. Melody Foess Raasch has more than 28 years of veterinary experience. After graduating with her DVM from the MSU College of Veterinary Medicine in 1993, she started her career as a small animal practitioner. Later, Raasch moved into industry, where she has worked for multiple popular pet food companies.

She has worked with The Iams Company and P&G Pet Care, and is currently a product performance evaluation scientist at the Royal Canin Pet Health Nutrition Center in Lewisburg, Ohio.

Near the start of Raasch’s career, she witnessed the most-extensive pet food recall; the melamine recall of 2007 directly impacted the brands she worked for, and she received numerous inquiries from worried veterinarians about the detrimental situation pet owners were facing. During this unfortunate event, Raasch became more interested in food safety, and was determined to incorporate it into her veterinary career. That’s when she decided to pursue the College’s Online Master of Science in Food Safety (MSFS) degree. “It was the perfect time to pursue a degree in food safety because of what was happening in the pet food industry,” says Raasch. “But to find out my alma mater had a food safety master’s degree program that was geared toward working professionals—it all aligned perfectly.”

During her time in the master’s program, she received the 2012 Edward and Mary Mather Food Safety Student Recognition Award for her final project, “The Impact of a Food Safety Certification Statement or Seal on Pet Food Packaging.” The Mather Award is given to one student per academic year who excels in the design and implementation of their applied food safety project, which often connects to students’ professional environments. Raasch graduated with a 4.0, and was the first veterinarian from a pet food company to graduate from the MSFS Program.

With this newly acquired food safety knowledge, Raasch was able to explore new and different career pathways. She uses her DVM and MS degrees daily. She understands specific, food safety-related medical concerns for pets, and uses this understanding when working alongside her colleagues. “I think it is unlikely I would be working in my current research and development role without this degree in food safety,” says Raasch. “My background in veterinary medicine has helped when planning field trials with veterinarians, and my education in food safety is a bonus that enhances my understanding of product development. The combination of both the DVM and MSFS is pretty unique.”

In her current position, Raasch conducts research trials that provide scientific evidence that Royal Canin and Eukanuba’s product claims are valid and the crucial information on product communications materials is factual.

Raasch also works in academia. Since 2013, Raasch has been a guest instructor for MSU’s MSFS Program, for which she leads the pet food module in the Introduction to Food Safety course. She also has served as an advisor in the Applied Project course, the final course for MSFS students, and has developed a one-credit elective in pet food safety. “It is such an honor to have been asked to be an instructor,” says Raasch. “I really enjoy working with the students each semester, and I am constantly learning from them as well.”

Raasch believes that veterinarians have a unique educational background and an important part in protecting the global food supply. “Whether you are a large animal veterinarian working with cattle or a veterinarian scientist researching products to keep our companion pets safe, we all have a duty and a role in keeping all food safe,” says Raasch.