PhD candidate Dr. Syeda Anum Hadi shares her journey, mission, and research in veterinary medicine.

As a PhD candidate at the Michigan State University College of Veterinary Medicine, there’s not much Syeda Anum Hadi, DVM, M.Phil, hasn’t already done. She is a Fulbright scholar and a published researcher who has received multiple awards and grants to support her education and research.

“One Health is the biggest priority for me. It’s important for me to not just conserve human and domestic animal health, but also wildlife,” says Anum.

She’s well on her way. From a childhood interest in wildlife to the working development of a multi-species diagnostic test for bovine tuberculosis, Anum’s journey encapsulates destiny, drive, and mentorship in veterinary medicine.

Dual-degree student Andrea Weinrick tells her story of veterinary school, motherhood, and finding her passion for animal, human, and public health.

The Animals have interested Anum since she was very young. However, she lived in a small house in Rawalpindi City, Pakistan, which meant that keeping animals was not an option for her. She found herself glued to TV shows like “The Crocodile Hunter” on Animal Planet. But she never thought she could make a career out of working with animals.

“My parents wanted me to become a human doctor. But destiny had a different plan for me,” says Anum. “One day, my dad told me that my favorite animal conservationist, Steve Irwin, had died due to a tragic accident. For the next three days, I just saw the repeat telecasts of Steve’s incredible life and his passion for saving the wildlife on Animal Planet. The work at Australia Zoo and the hospital Steve created was absolutely inspirational.

“I began to wonder what the people who were treating the boa constrictors, koalas, elephants, and alligators had studied,” Anum continues. “At that time, I found real-life, national inspiration in the form of the legendary Dr. Arshad Haroon Toosy, who was the director at Lahore Zoo and was a veterinarian by profession. I had found the right profession for myself—veterinary medicine!”

“Maybe it was an emotional decision, but it was the best decision of my life,” Anum adds. “For me, it was the perfect combination of respecting my parents’ wishes and my change of heart.”

Anum says veterinary school has been the most gratifying experience of her life, from treating 500-kilogram—roughly 1,100-pound—water buffaloes to cute, furry puppies. During her last year of veterinary school at Pir Mehr Ali Shah Arid Agriculture University in Rawalpindi, Pakistan, she took an epidemiology and zoonotic disease course. Her mentors, Dr. Manzoor Hussain and Dr. Zahida Fatima, exposed her to infectious disease control practices for rinderpest, foot and mouth disease, and avian influenza.

“I realized I could contribute even more toward wildlife conservation by focusing all my energy on a zoonotic disease that affects humans and animals alike,” says Anum.

Anum went on to earn her Master of Philosophy in Veterinary Epidemiology and Public Health from the University of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, Lahore, Pakistan. There, she delved into her love for zoonotic diseases and chose to study two main dairy colonies and their prevalence of bovine tuberculosis. Soon after that, she worked as a field veterinary officer, as well as a third-party surveillance officer for the Dengue Control Program in the Livestock Dairy Development Department in Punjab, Pakistan.

After a year, Anum wanted to expand her work on zoonoses and One Health. In 2016, she left Pakistan on a prestigious Fulbright scholarship and arrived in St. Paul, Minnesota to begin her doctoral studies at the University of Minnesota in Dr. Srinand Sreevatsan’s laboratory. One year later, Sreevatsan accepted a chair position at the MSU College of Veterinary Medicine, and Anum followed him to East Lansing, Michigan.

Since then, she has presented her research findings at multiple conferences and won numerous awards. In February 2020, Anum won the three-minute pitch competition at MSU’s 12th Annual Graduate Academic Conference, hosted by the Council of Graduate Students. Sreevatsan was present for her victory; Anum says this type of support from a mentor is invaluable.

“The fact that Dr. Sreevatsan came to support me, along with my fellow graduate students, was just incredibly humbling,” she says. “And winning in front of all my friends and mentor was the best feeling ever!”

In Sreevatsan’s laboratory, Anum continued to study bovine tuberculosis (bTB), which is caused by Mycobacterium bovis. bTB, a disease that is chronic and highly contagious with known zoonotic potential, has low prevalence in the US, but is endemic in Michigan. This is because of the white-tailed deer, which acts as its wildlife reservoir. bTB can be transmitted to humans through consumption of unpasteurized dairy and meat products from infected cattle or through close contact with infected animals.

In addition to its status as a public health issue, bTB also is an animal welfare concern and an economic challenge. bTB-infected cattle are not treated. Instead, they must be culled to stop the spread of the disease to other cattle and humans. The cost to producers is monumental. If even one cow has bTB, the entire herd must be quarantined until confirmatory testing can take place. During this time, no animals or milk may be sold. If the infection is confirmed, the entire herd must be depopulated.

For successful control of bTB, timely, cost-effective, and highly specific herd testing is critical. Current diagnostics fall short. The tuberculin skin test can result in false positives because it cannot differentiate between members of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTBC), versus the non-MTB members. In addition, interferon (IFN)-gamma tests, though very sensitive, require expensive infrastructure, whereas tuberculin skin tests are time-consuming and labor-intensive.

“For the tuberculin skin test, you have to restrain the animal, then inject it with tuberculin and wait 72 hours. Then, you have to go back to the farm and read the results,” says Anum. “If the result is positive, the animal is classified as a suspect, and then a USDA-certified veterinarian has to go and perform a comparative tuberculin skin test to differentiate whether it was an environmental mycobacterium or potentially infectious mycobacteria. But even then, it’s not confirmed. You have to collect samples and send them to the lab for confirmation.”

To overcome these problems, Sreevatsan’s laboratory is developing a next-generation diagnostic test for bTB. Instead of using host responses as a testing mechanism, they’re focusing on pathogen responses to enhance specificity of test results. This also will make the test compatible with a wide range of species.

Sreevatsan’s team discovered three MTBC-specific proteins (Pks5, MB2515c, and MB1895c) that circulate in infected animals. For the new diagnostic test, these are pathogen-specific biomarkers—in other words, surefire identifiers of bTB.

Their test also will use aptamers (single-stranded DNA segments) as the detection molecule. Aptamers’ simplicity of structure, specificity, low cost of mass-scale production, and zero batch-to-batch variation gives them the advantage over antibodies. Additionally, aptamers are generated without animal models, which makes them a more humane option in mass-scale production.

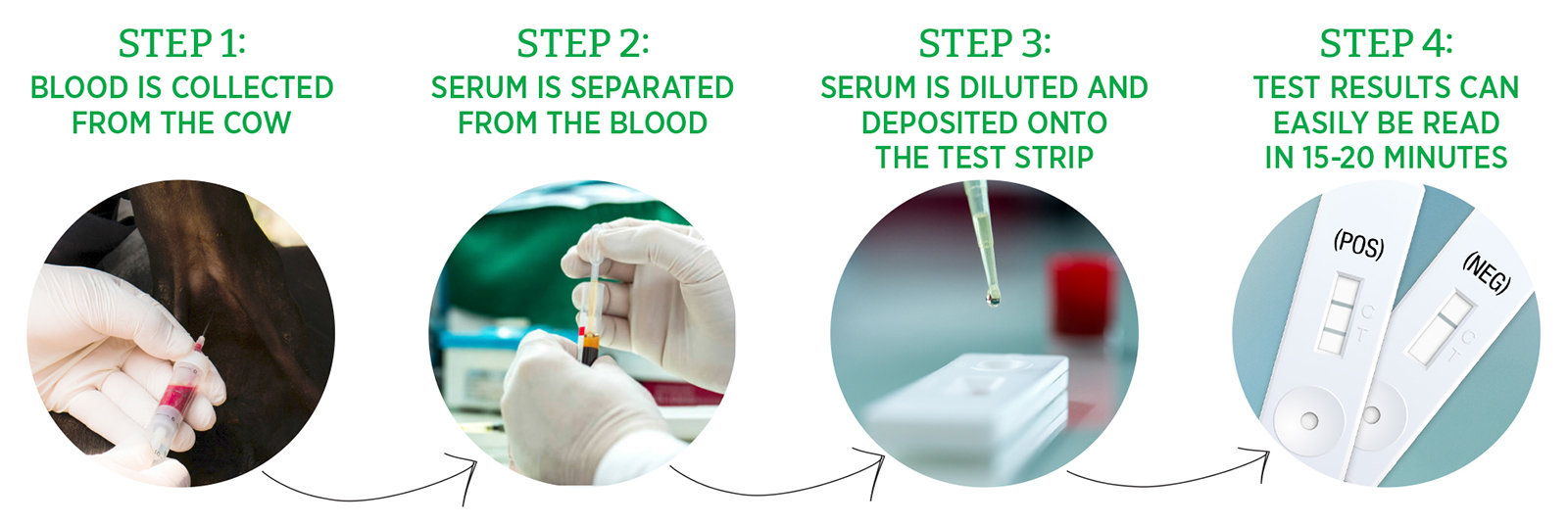

Anum exposed Pks5, their strongest bTB biomarker, to an aptamer library. She found two aptamers specific to Pks5 that are now being tested. Her hope is to use one of these aptamers in the new testing device, which will be similar to a pregnancy detection strip—simple, cheap, and rapid, with the added advantage of being highly specific.

“Our ultimate goal is to take these findings and create a point-of-care device to be used in the field,” Anum says. “Veterinarians or trained personnel can collect a cattle blood sample, separate the serum, put the serum on the new test, and get easily interpretable results within a few minutes. We’re still in early stages, but our hope is that this new diagnostic assay will be rapid, cost-effective, usable on multiple species, and highly specific. If we succeed, we’ll be making a tangible difference in domestic animal, wildlife, and human health.”