Playing Chicken with a Virus

By Jamie DePolo

By Jamie DePolo

The outlook was bleak. Thought to be caused by a virus, a highly contagious disease was paralyzing and then killing hundreds of thousands, which was affecting the economy of almost every country in the world. Top scientific minds were working furiously to isolate the cause and develop a vaccine.

While this dark scenario could be lifted from present headlines, it actually occurred in the mid-1900s. Chickens, not people, were the victims, and for those in the broiler and egg industries, the economic devastation was staggering. One study estimates that the ultimate worldwide cost was $1 billion per year.

Named for Hungarian physician Jozef Marek, who first described the disease in his backyard roosters in 1907, the specific cause of Marek’s disease remained a mystery until the late 1960s.

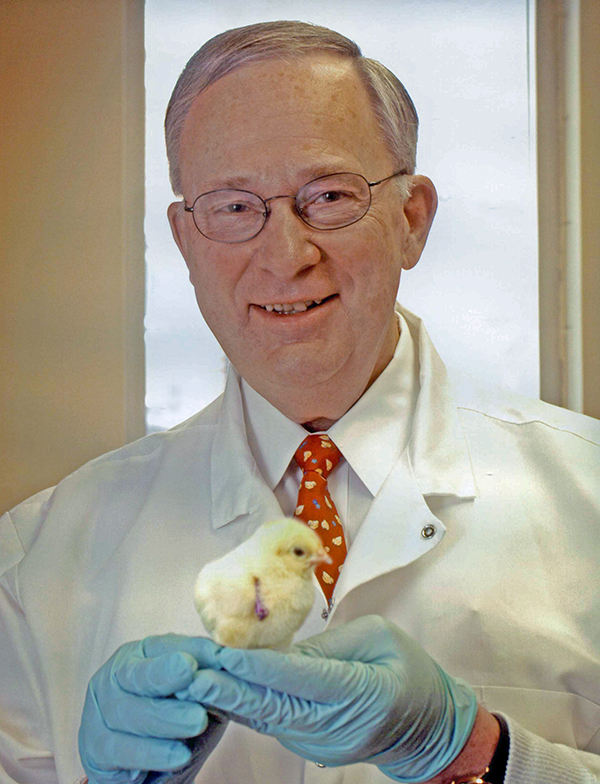

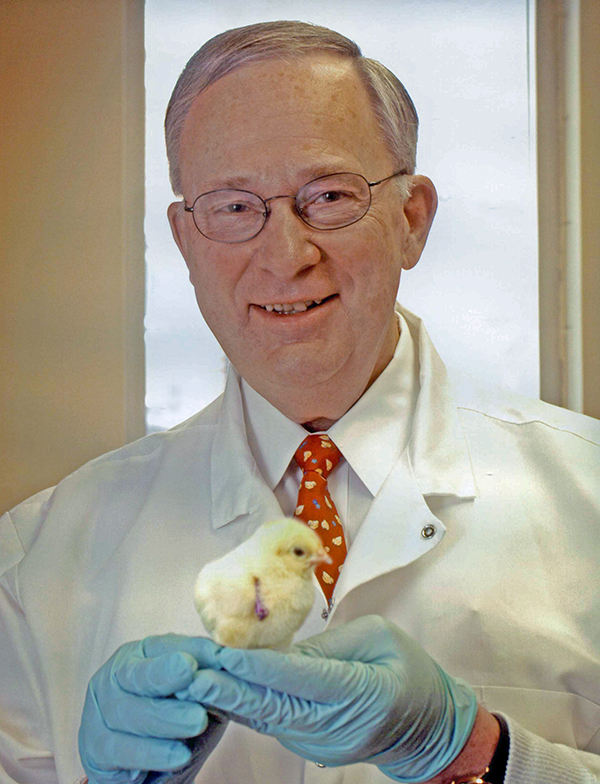

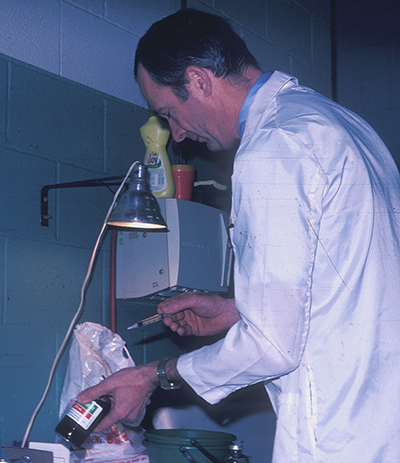

Thanks in large part to the ground-breaking research of Richard Witter (DVM ’60), who helped isolate the virus, the world learned that the poultry infecting Marek’s disease was caused by a herpesvirus and that certain breeds, such as leghorns, were more vulnerable to the disease. Witter then helped to create the first vaccine produced in the United States for Marek’s disease in 1969, which was introduced to the world in 1970. There is no treatment for Marek’s disease; once an animal becomes infected, it is infected for life and can shed the virus and infect other animals. So, vaccination is the main strategy to control the disease.

“I really had no time to bask in my accomplishments,” Witter recalls modestly. “There was so much going on; we knew that many more steps would have to be taken. A lot of people said it was huge. There were a lot of things that fell into place at the right time and it worked out well.”

Looking at the current pandemic through his virologist’s lens, Witter sees certain parallels between COVID-19 and Marek’s disease, though he is quick to point out that his research took place 60 years ago, so there can’t be a direct comparison.

“They are both high-profile virus infections, causing pandemics that were/are causing major economic loss in almost all countries in the world, not to mention the lives lost,” he says. “And work on vaccines for both have been conducted in a state of national emergency. In my case, it was chickens; now it’s people.”

“Much of my research on Marek’s disease focused on vaccine development and improvement,” he continues. “When comparing vaccines, I had the advantage of being able to subject vaccinated animals to a substantial, virulent challenge. I could work with groups of many chickens in each treatment with appropriate controls and had the capacity to replicate experiments several times. Even so, it was amazingly difficult to detect small differences in vaccine efficacy.

“We are right at the beginning of similar trials on candidate COVID vaccines,” he adds. “I would predict that more than one product will prove to have some efficacy and, thus, that it will become important to know which of the several candidates is better. But this may not be an easy task.”

The only child of two Michigan State-educated parents, Witter followed in his father’s footsteps and earned his DVM from MSU. His home state of Maine had an active poultry industry, which helped foster his research interests.

“My dad felt that the chicken was just as important an agricultural species as cattle or hogs,” Witter explains. “That idea stuck with me.”

Witter’s father was the chairperson of the Department of Animal Pathology at the University of Maine for many years.

“I never considered going into veterinary practice,” he adds. “I was more interested in academic applications.” Witter went on to lead the U.S. Department of Agriculture-Agricultural Research Service Avian Disease and Oncology Laboratory on East Lansing’s Mount Hope Road for 23 years. In 1998, he was elected to the National Academy of Sciences for his accomplishments, a phone call he says changed his life.

“Any veterinarian would be surprised to get that call,” he says. “When I was elected, there were very few veterinarian members [currently there are six]. Members are considered to be the very best scientists—I never considered myself to be in that category, but I feel extremely fortunate to be a member. I have tried to be a good representative of our profession and an active participant in the organization.”

Witter followed in his father’s footsteps one more time: In 1985, Witter was honored with the MSU College of Veterinary Medicine’s Distinguished Alumni Award for his accomplishments. His father received the award in 1970.

After 38 years with the Avian Disease and Oncology Lab, Witter officially retired in 2002. He isn’t in the lab every day, but is just as busy as ever, reading journals, voting on National Academy candidates, actively participating in the American Association of Avian Pathologists, and tending his extensive vegetable gardens, one of his many hobbies. Witter says his career has focused on three goals: advancing knowledge, promoting the institution of science, and passing the torch.

To help achieve his final goal, he and his wife, Joan (bachelor’s degree in home economics, 1960; master’s in adult and continuing education, 1987), whom he met at MSU, established an endowed graduate fellowship designed to assist veterinarians earning a doctoral degree and whose research focuses on infectious or other diseases of animals.

“Dick and I are committed to helping CVM students initiate and complete graduate programs during this time when resources are tight and the need for scientific discovery is greater than ever,” Joan says.

“The purpose of the fellowship is to prepare veterinarians for careers in animal disease research,” Witter says. “We also hope that the people who receive the fellowship will feel in some measure that the torch has been passed to them by someone who has walked the same road.

“My goal in creating the fellowship was to encourage veterinarians to continue in research careers, like I did, and to focus specifically on diseases of animals, also like I did. It just seemed fitting to use the resources I gained during my wonderful career to help guarantee there are vet students who will follow a similar path.”