By Brittney Urich

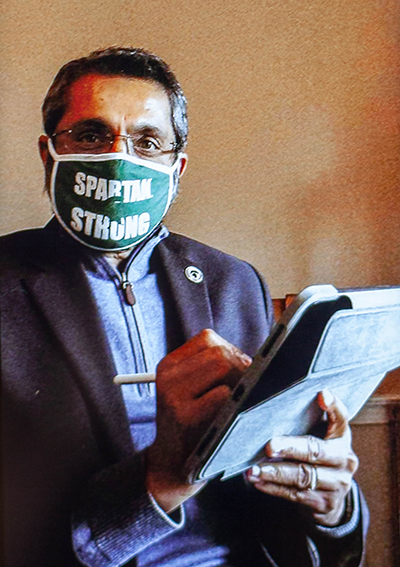

For most of us, the COVID-19 pandemic is unknown territory. For Dr. Srinand Sreevatsan, associate dean of Research and Graduate Studies at the MSU College of Veterinary Medicine, this is a familiar landscape. It is another, important opportunity to partner with health professionals across different disciplines to better understand zoonotic and reverse-zoonotic transmissions.

“About 70 percent of the emerging human infections are of zoonotic origin,” says Sreevatsan. “Humans, animals, and the environment are inextricably linked to one another.”

Sreevatsan has researched infectious diseases for his entire career. He focuses on the pathogenomics and molecular evolution of several zoonotic pathogens, especially mycobacteria and influenza. He is an ambassador for One Health, a transdisciplinary effort to improve the health and safety of food products, animals, humans, and the environment. In 2018, he co-published a paper titled “The Science Behind One Health: at the Interface of Humans, Animals, and the Environment.” The paper focuses on the challenge humans face as growing demands for resources for an ever-expanding population threaten the existence of wildlife populations, degrade land, and pollute air and water.

“One Health is a very important aspect of the work we do as healthcare professionals,” says Sreevatsan. “It’s built into our veterinary training. In order to achieve health for humans, animals, and the environment, we need to take an interdisciplinary approach to healthcare.”

These transdisciplinary efforts are made at local, national, and global levels, which is especially critical as we work to uncover the cause of the COVID-19 pandemic. “To understand the origins of this pandemic, we have to partner with other healthcare professionals,” says Sreevatsan. “We need disease ecologists who study infectious diseases, evolutionary biologists who comprehend how viruses evolve in different types of hosts and environments, and veterinarians who understand animal health and behavior. Identifying the origins and evolution of the pandemic can help us determine how we can potentially control it.”

Veterinarians are key in advancing our understanding of the reverse-zoonotic mutations of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. “With a pandemic on hand, we need to pay attention to the ways we interact with animals,” says Sreevatsan. “We know that other animal species, such as cats, are susceptible to the same coronavirus we are.”

A virus evolves each time it undergoes zoonotic or reverse-zoonotic transmission. These changes help optimize the viral molecules to aid in replication in a new host and likely the jump from species to species. As that happens, the virus becomes highly efficient, increasing the risk of transmission. This poses a danger to multiple populations. But veterinarians, who are trained to understand aspects of zoonotic infectious diseases that are not part of conventional medical training, can lend critical insights to conversations regarding public health and policy.

“Veterinarians bring a unique interpretation to the world of infectious diseases in animals and humans,” says Sreevatsan. “We understand that certain infections have specific characteristics when they’re transmitted from animal populations to human populations.”

Additionally, veterinarians have always been well-versed in herd and population health. They are trained to understand infectious disease progression and transmission in production animals.

“Our perspective as veterinarians can be extremely valuable in population medicine and vaccinology,” says Sreevatsan. “We understand the dynamic nature of viruses, which is why we have developed production systems to aid in the prevention of transmission of diseases. We understand when to deploy vaccines, how to deploy them, how to curtail virus spread from animals to humans, and how to help mitigate the spread of viruses within human populations.”

Sreevatsan’s collaborations with other healthcare professionals have been successful in the past. He has written about mycobacterial diseases with infectious disease physicians and the United States Department of Health and Human Services. Their work focused on identifying drivers of bacterial transmission among animals and humans in specific ecosystems. In 2009, he partnered with the Department of Health and Human Services’ physician and veterinarian during the swine flu pandemic.

“When the H1N1 pandemic first occurred, the initial thought was that it was caused by a virus that originated from swine,” says Sreevatsan. “We discovered that the virus had remnants of viruses infecting multiple host species. When H1N1 was transmitted to pigs, it led to the emergence of a new strain called H3N2 variant that was infectious to both pigs and humans.”

Sreevatsan and his colleagues studied the pigs that were infected with H3N2 to understand the potential risks, as well as how they could mitigate the risk of transmission of H3N2 and the transmission of H1N1 back into pigs.

“Our collaboration with the Department of Health and Human Services was incredibly fruitful,” says Sreevatsan. “We were able to draw on a lot of commonalities in infectious diseases. We created policies around exhibiting pigs in state and county fairs and introduced critical control points to prevent transmission events between animals and humans.”

11 years later, there is even more opportunity for transdisciplinary partnership during the COVID-19 pandemic. Veterinarians have a wealth of knowledge about animal coronaviruses. Because all coronaviruses have the same genome organization, veterinarians’ knowledge of animal coronaviruses can help shed light on how public health understands human coronaviruses. “With our knowledge of animal coronaviruses, we know what to expect in terms of clinical manifestation and how the disease spreads,” says Sreevatsan. “The current asymptomatic spread is primarily because we don’t know when to sample people. But we can apply the best practices of herd health to this situation and provide information to public health officials around how coronaviruses are managed in veterinary medicine. They can apply that knowledge to human and public health.”

Sreevatsan believes there needs to be a multifaceted response to the pandemic that takes into account global health issues, climate change, migration, and poverty. This type of response will require collaboration from a range of healthcare professionals and other experts.

“Most infectious diseases emerge in poverty and amplify. They are so tightly connected to social aspects, which is why we need more than veterinarians, physicians, and virologists to tackle this pandemic,” says Sreevatsan. “We need environmental scientists and social scientists who can bring in their perspectives and provide education about the importance of proper health behaviors to prevent the transmission of this infection.”

What do you think of the new, all-digital Perspectives Magazine? Take our short, anonymous survey and let us know.

Survey