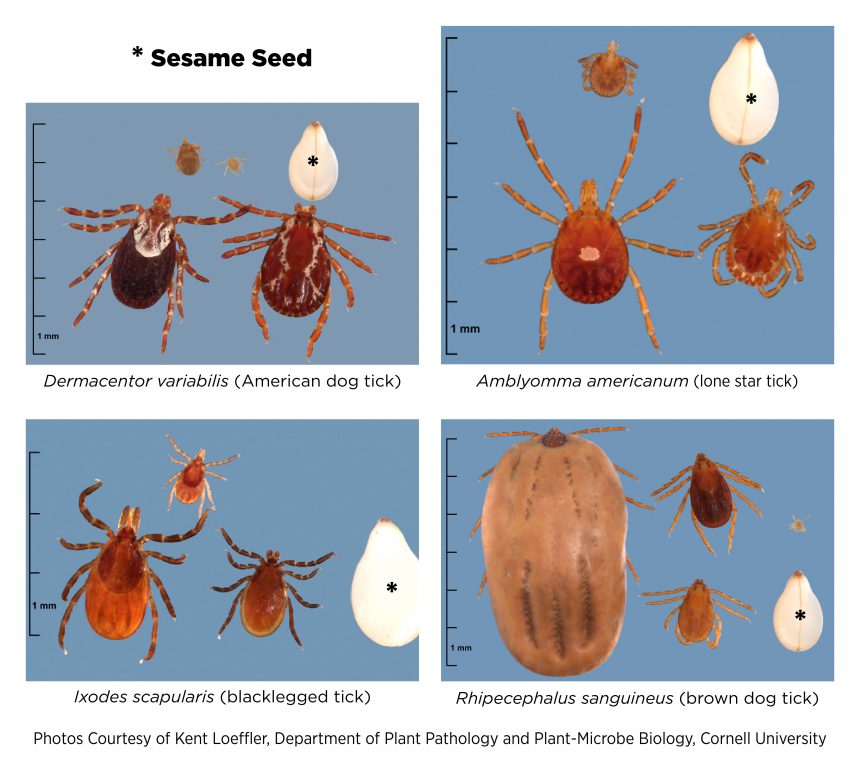

Anaplasmosis, babesiosis, ehrlichiosis, Lyme disease, and Rocky Mountain spotted fever can be spread by ticks to humans and various species of livestock and companion animals. Ticks are arachnids, not insects. After hatching from an egg, the tick must have a blood meal to advance from one life stage to the next. The four stages in the life cycle of a tick are the egg; which hatches as a small, six legged larva; which molts to become the slightly larger, eight legged nymph; and after the nymph has a blood meal it molts to become an adult tick and the life cycle is completed. Although larva and nymph stage ticks feed on pets and can transmit disease, those life stages are small in size and it can be difficult to find them on a pet. The adult stage is larger in size and is more easily found, especially if the tick is partially engorged with blood. Most ticks submitted to our laboratory are adults.

A Tick for All Seasons

Ticks can be found on pets throughout the year. However, seasonal trends in number of ticks and in species of tick submitted are seen here at the lab. The months from April to July, and October to November are when the highest numbers of ticks are submitted.

The Ixodes scapularis tick in the eastern U.S. and Ixodes pacificus tick in the western U.S. are commonly termed deer ticks, or blacklegged ticks, and can carry Lyme disease caused by Borrelia burgdorferi. Borrelia mayoanii, a recently identified bacterium which also causes Lyme disease, is found in Ixodes scapularis ticks in the upper Midwest. Anaplasmosis caused by Anaplasma phagocytophilum and babesiosis caused by several species of Babesia are transmitted by Ixodes ticks. Adult Ixodes ticks from Michigan are submitted most frequently from late February to late May, then again from late September to early December.

The months of April to August yield the most submissions for Dermacentor variablis, also known as the American dog tick or wood tick; which can carry Rickettsia rickettsii, the cause of Rocky Mountain spotted fever. The summer months are when adult Amblyoma americanum ticks (lone star tick) are submitted. Those ticks can carry Ehrlichia spp. Finally, Rhipicephalus sanguineus, the brown dog tick, which can carry Babesia spp, Ehrlichia spp, and Rickettsia spp is adapted to live indoors and may be submitted any time of the year.

Tick Removal

We recommend that the pet is taken to a veterinarian for tick removal which is best done following the instructions from the Centers for Disease Control (https://www.cdc.gov/ticks/afte...) or the American Kennel Club (www.akc.org/expert-advice/health/how-to-remove-tick-from-dog/). Please remember—be careful when removing a tick. Try to not squish the tick and get blood on yourself (disease producing organisms may be in the blood) and try to keep the head of the tick attached to the body of the tick. An intact head on the tick can aid in identification which is important for determining which diseases are of concern. If the tick cannot be identified at the veterinary clinic, the tick can be sent to the laboratory for identification (test code 60066).

Submitting a Tick for Identification and/or Testing

First, do not squish the tick. Preferably, place the intact tick in a screw top container or empty blood collection tube with a tight fitting stopper. Ticks can escape from a push-andtwist-top pill bottle. Do not place the tick in formalin solution and, please, do not stick the tick to a piece of tape. If the tick is dead and dried out, place it in some saline solution. The tick can be shipped without an ice pack. When the tick is identified, either at the veterinary clinic or at the laboratory, a tick PCR assay (test code 60065) can be done to detect disease-causing organisms that may be borne by the tick.

Overall, of the PCR diagnostics performed at the laboratory, positive results are most likely for Rickettsia spp. [Note: A Rickettsia sp found in a tick may not be pathogenic for people or animals]. If we detect a Rickettsia, we will perform a PCR assay that is specific for Rickettsia rickettsii at no extra charge. The next most common finding is Babesia odocoilei, which is known to infect deer and elk, but is not known to cause disease in pets. An increasing number of the PCR assays done at the laboratory for Borrelia burgdorferi are positive, as this organism is spreading and becoming more common in the Great Lakes region. We also detect Anaplasma phagocytophilum in a few ticks each year and expect this organism to become more common in our area.

Tick-Borne Diseases in Animals

Symptoms for tick-borne diseases in animals are typically non-specific and may include fever, weakness, lethargy, lameness, lack of appetite, vomiting, and diarrhea. While much of the veterinary focus on tick-borne diseases tends to be on dogs, remember that many species, including horses, are also susceptible. If a dog, cat, or horse is suspected of having a tick-borne disease, the laboratory offers several tests to aid in diagnosis.

The same PCR assays that are done on ticks to detect the organisms that cause tick-borne disease can be done on a blood sample (purple top, EDTA tube) collected from the pet. Those tests are Anaplasma PCR (90051), Lyme PCR (60059), Babesia spp PCR (60003), Ehrlichia PCR (60048), and Rickettsia PCR (60060). The PCR tests are best done in the acutely affected pet before treatment is started. After treatment is started, or in the chronically affected pet, the preferred tests would be serum based indirect fluorescent antibody (IFA) tests such as the Tick Borne Disease Antibody Screen (60013), which includes all of the tick-borne diseases mentioned here. Tests that can be ordered individually are Anaplasma phagocytophilum IFA (60033), Babesia canis IFA titer (60001), Babesia gibsoni IFA titer (60046), Ehrlichia canis IFA titer (60008), Lyme IFA (60014), and Rickettsia rickettsii IFA (60021). We test about 100 horses each year for Lyme disease and anaplasmosis using the Equine Tick Core Panel, 60989. An antibody titer is reported for all IFA tests. This allows for meaningful comparison of acute and convalescent samples of serum.

We are often asked whether a pet can acquire a tick-borne disease even when a tick has never been found on the animal. Unfortunately, the answer to that is question is yes. Remember that the larva and nymph stages of ticks are very small and easily missed when a pet is examined for ticks. Also, we have received several engorged ticks that were not found on the pet, but were found in the house in areas frequented by the pet. So it is possible even for an engorged tick to escape detection on a pet. Prevention, identification, diagnostic testing, and early treatment for infection are keys to decreasing the incidence of severe illness and fatalities.

As always, if you have questions, need help ordering tests, or want more information on testing; call the laboratory. We enjoy the opportunity to talk with our clients!

For More Information

In addition to national data provided by the CDC (https://www.cdc.gov/ticks/), look for state and/or local information provided by government agencies such as Community Health/Health and Human Services and Agriculture for information on your specific region.

Client Education Resources Available!

A guide on ticks and tick-borne diseases for clinicians and pet owners is available. It includes quick tick facts, resources for additional information, and resources specifically for our Michigan clients. Other guides for pet owners are also available and include leptospirosis, canine mast cell tumors, canine influenza, and equine metabolic syndrome. Please let us know if you have topics you’d like us to cover by contacting Courtney Chapin, chapinco@cvm.msu.edu.