In 1910, the Michigan State University College of Veterinary Medicine was established as a four-year, degree-granting program; the last full Doctor of Veterinary Medicine (DVM) curriculum reinvention took place in 1992. In the decades since, it has received smaller, periodic updates.

Much has changed in the landscapes of both veterinary medicine and medical education since 1992—research, knowledge, and technology—resulting in the need for a curriculum overhaul so the College could continue to provide students with the best education possible. In 2016, the College heeded this call and undertook the reinvention of its DVM curriculum.

“It’s a new world compared to when the legacy curriculum was created,” says Dr. Susan Ewart, faculty excellence advocate, special assistant to the dean, and professor for the College. Ewart has been a faculty member at the College since 1995 and was one of the first faculty members to teach in the new curriculum. “The reinvention takes into account the increased amount of information available and the new ways technology has made it accessible. It was done to address the changing needs of students.”

The College partnered with MSU’s Hub for Innovation in Learning and Technology and used evidence-based educational models and methodology to transform the traditional, lecture-based curriculum, embrace a competency-based model, and introduce a flipped classroom approach that emphasizes active and case-based learning. The focus in the new curriculum is to prepare students with the technical knowledge and entry-level professional competencies necessary to be day-one-ready veterinarians.

Flipping the Classroom

The curriculum reinvention used Bloom’s Taxonomy, a sequence of cognitive skills created by Benjamin Bloom, as its educational framework. This model breaks up learning objectives into a hierarchy, where remembering is the lowest level of comprehension and creating is the highest.

Most people are familiar with a traditional teaching model: a professor at the front of the classroom lectures to a group of students. This is basic knowledge transference—the lower levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy, remembering and understanding—when an expert attempts to upload what they know into learners’ brains. A flipped classroom approach is different because it doesn’t dedicate much class time to these lower levels of learning.

In a flipped classroom model, the lower levels of learning are completed before students ever set foot in the classroom. Before each class period, students are required to review prep material—readings, slides, and recordings of mini-lectures that their professors prepared—and then complete a quiz to test their understanding of that material. Students arrive in each class already knowing the basics. Class time is spent on higher levels of learning—applying, analyzing, evaluating, and creating—all in the presence of an expert. Ewart speaks highly of this approach to teaching.

“In the new curriculum, prep work allows students to come prepared with a basic understanding of introductory material for the day, and then we can focus on what is complicated and challenging—what parts do we need to pick apart and put back together—where are the struggles?”

Now, instead of starting with a lecture, Ewart begins her classes with a thought-provoking activity based on material the students have already learned before coming to class. Then, the class works through a series of prompts in groups, including questions revolving around specific clinical cases, before reconvening as a class to work through the ramifications of their conclusions.

Ewart enjoys teaching in the new curriculum because it is so interactive. “In a traditional lecture-based curriculum, it’s more of a one-way conversation—now, there’s lots of feedback and you can really get a sense of where the students are at.”

Ewart believes this approach really pushes students into higher levels of learning. “It’s a series of conversations they first start together, where I’m not telling them the answers. Instead, I turn it around and say, ‘You tell me, why is it that way? What if it’s not that way? What happens?’ And that encourages them to engage with the material at a higher level.”

Focusing on Day-One Competencies

One of the major problems with education is retention. Students learn the information in order to pass exams, but have trouble recalling much of what they learned later, after they have crammed in yet more information to pass different exams. Part of the problem with retention is that there’s so much knowledge.

Since the first professional veterinary school was established in 1761, the amount of veterinary medical knowledge has grown far beyond what one brain could ever hold. Instead of trying to cram as much information as possible into students’ brains, the reinvented curriculum focuses on what a student would need to know on their first day as a general practicing veterinarian. With help from the Hub, faculty focused on entry-level professional and clinical competencies, while they built the new courses.

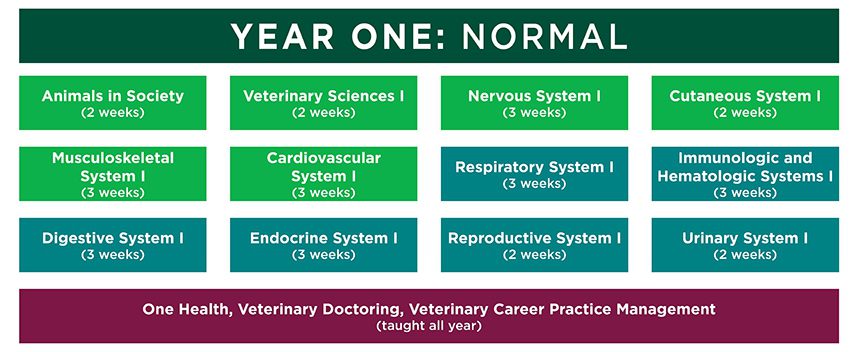

This competency-based approach also overhauled the course schedule. Instead of multiple courses on different topics concurrently throughout a semester, courses are broken up into smaller two- and three-week chunks, when students are only taking one major course at a time.

Ewart says that while students are still learning a lot of information, she does see benefits from the new structure. “Before, students naturally felt pressed to study from exam to exam. They often didn’t have the time to prepare for, or even attend, a particular class because they had an exam in a different class. Now, there is less competition for their time, and students can focus on fully learning one topic at a time.”

Each course builds on the one before it. This helps with knowledge retention and skill building. Year one focuses on normal body systems and how the systems work in a healthy animal, while year two dives into abnormal body system function. The first semester of year three focuses on clinical reasoning, preparing students for the clinical rotations comprising the second half of year three and all of year four.

Increased Active Learning

When looking at knowledge retention and competencies, it is important to look at not just the knowledge students will need, but also the skillset necessary for a day-one-ready veterinarian. Medical education, by its nature, always involves a certain amount of hands-on learning, but often that hands-on part comes later in the curriculum.

In the traditional model, students might learn something in year one and not apply that knowledge in a hands-on clinical situation until year two or even year three of their education. In the new curriculum, that time gap is removed. Students learn and practice clinical skills—with models and live animals—in their very first course.

With Ewart, who leads the first year respiratory course, students learn the anatomy and physiology—how the lungs are structured, how the respiratory system functions to move oxygen—and then they learn how to use a stethoscope, getting firsthand knowledge of what lungs should sound like in different animals, and learning how to use a pulse oximeter (a non-invasive test used to measure the oxygen level of the blood).

This helps with knowledge retention and helps students learn the process of thinking like a clinician. “It isn’t just about knowing the information,” says Ewart. “It’s about knowing how to look at the information a patient presents, knowing what questions to ask to find missing information, and being able to work your way to a diagnosis.”

Creating Lifelong Learners

Because students are required to do much of their initial learning independently in a flipped classroom model, they learn how to take charge of their own education. Ewart believes that in addition to creating day-one-ready veterinarians, the reinvented curriculum has the added benefit of creating lifelong learners.

In a world with much more information than one person could ever know, Ewart says this is a necessity to succeed. “Veterinarians need to be regular consumers of new information,” she says. “They need to know how to find it and how to place it into context in the background of their current knowledge. They need to have a basic understanding that will direct them to what they should look at further.”

An important part of the new curriculum is providing students with the tools to both find new information and to interpret it, as they will need to do for cases on a regular basis. Ewart believes this is an important part of the new curriculum because it teaches students that they aren’t going to learn everything in school, that they are going to need to continue learning their entire career. “If we teach our students to think, to discuss cases with their team, to problem solve, this is a more effective way to create lifelong learners.”

It Takes a Team

Teamwork is an essential part of the new curriculum. It started from the very beginning, with faculty who worked in committees to identify the competencies on which the reinvented curriculum would focus. It continued as instructional designers from Hub worked with the College’s faculty to design and create the curriculum, course by course. The team grew as a group of incoming DVM students piloted two first-year courses to help faculty and the instructional design team improve the courses before the new curriculum launched in the fall of 2018.

The courses themselves also are run by a team. Each course is run by one faculty member, called a moderator, who works with a course team comprised of other faculty members to develop and run the course. Most of the time, the instructors are made up of the course team, but they also may bring in other instructors for specific classes.

This educational model involves many live animal labs, which offers clinicians and students the chance to work much more closely together. Clinicians who might not have seen students until their third or fourth years of veterinary medical school now are invited to participate in labs with first-years. “They work with students, have discussions, talk about their perspective, all without a course-long time commitment on their part,” says Ewart. “It is a chance for the whole community to come together and build relationships from the very beginning of a student’s time with the College.”

Spartan Story: The Connector

Dr. Susan Ewart is the quintessential teacher. She wants to listen to what you have to say just as much as she wants to share her knowledge with you. The passion for her work is clear in her voice, her facial expressions, and her hand gestures as she talks about everything from her early love of horses to teaching to research. She moves easily between discussing how she tried to convince her mother to keep a horse in the small lot of their metro Detroit home as a child to explaining how the respiratory tract works.

She has been an animal lover for longer than she can remember and grew up a “typical, horse-crazy girl.” (Her office contains a few trophies from those horse-crazy days.) She also liked math and science in school, so pursuing veterinary medicine was inevitable.

She attended MSU for both her undergrad and her DVM, after which she went to West Lafayette, Indiana and worked for an equine surgeon, who’d left Purdue University to run his own practice. She came back to MSU for her residency and fell in love with academia. Knowing she needed more research skills, she went to Johns Hopkins University for her PhD to specialize in the respiratory system.

In 1995, PhD in hand, Ewart returned to MSU for a job in equine medicine. While running equine medicine clinics, she also started a research program looking at the genetics of respiratory disease. She received NIH funding for her work and transitioned out of clinics to focus on research.

Now, in addition to teaching in several courses for the DVM curriculum and continuing her own research, she co-directs the Summer Research Program for veterinary students and the Biomedical Research for University Students in Health Sciences (BRUSH) Summer Research Program for students from populations underrepresented in biomedical research.

She also enjoys being a faculty excellence advocate and special assistant to the dean. In these roles, she works through the faculty search procedure, the annual review, and the reappointment, promotion, and tenure processes to ensure all the College’s policies and practices are appropriate at each stage of the process.

A large chunk of her time is spent mentoring junior faculty, her students, and the research students. Ewart says she likes facilitating the education and career paths of others. “I’m also a superhero,” she says as she laughs in a this-is-silly-but-I’m-proud-of-it kind of way. “I’m The Connector.” She considers her superpower to be the fact that she is well-connected, and she uses that network to help others connect to the people and resources they need.

Her favorite part of being a veterinarian is the One Health aspect of this very versatile career path. “I like that my skills allow me to be translational, to advance both animal and human health. The respiratory system also brings you into air quality—into the environment, into policy, everything we need to do to protect our health, animal health, and the environment for future generations to come.”

Ewart takes a moment to seriously consider before she talks about her favorite part of being a Spartan. “We don’t rest on our laurels. We work hard every day, we reinvent ourselves every day, we show up and make progress every day.”