In the next few years, several departments were created: anatomy, animal bacteriology and hygiene (known today as microbiology), medicine, bacteriology and pathology, pharmacology, and surgery. Graduate courses also were added in the Departments of Anatomy and Pathology, so that veterinarians could pursue graduate studies.

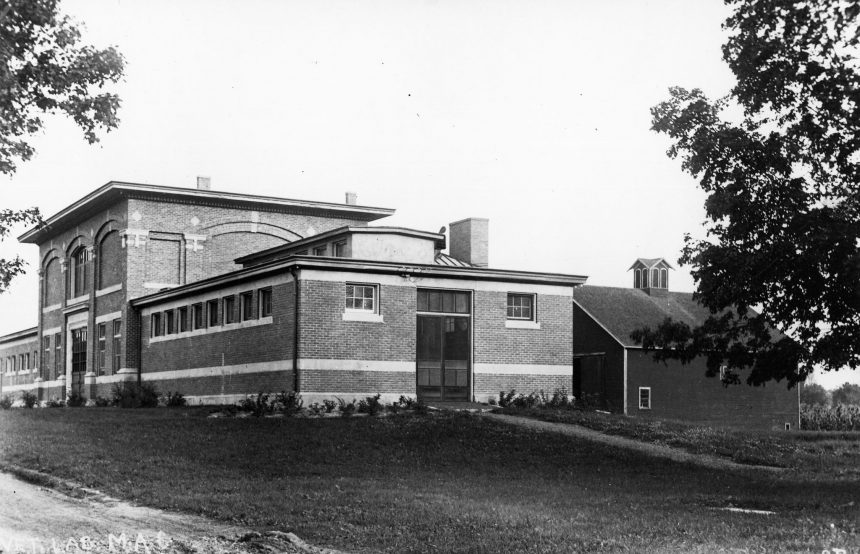

The Surgery and Clinics building was completed in 1914 at a cost of $25,500 and occupied in January 1915 on the same site as the present-day Giltner Hall. This facility was the third building dedicated to veterinary medicine. The others were the veterinary laboratory built in 1855 and the Bacteriology Building completed in 1902.

World War I left its mark on veterinary education. Because the horse was still an important factor in military campaigns, many veterinarians were needed to care for them. Dean Lyman's report to the president for the year 1917 reflects that demand: "When this country entered the world war, more than fifty percent of our graduates in veterinary science were in active general practice; including this year's graduating class, there are at this writing 87 percent in military service, and this absolutely by voluntary enlistment."

Another significant effect of the war was that veterinary officers, who were often closely associated with medical officers, came to realize that, as a rule, the quality and breadth of their education suffered by comparison. This later became an argument for strengthening veterinary education.

In 1919, Dean Lyman reported erosion of enrollment by almost 50%. About 80 percent of the upper-class veterinary students joined the Medical Enlisted Reserve Corps. Most of the faculty returned from the war effort later in the year and restored a degree of stability to the programs.

Dean Lyman took a leave of absence in June 1919 and later resigned, effective January 1, 1920. During his absence, Dr. Frank W. Chamberlain, professor of anatomy and physiology, was placed in charge, and—upon Lyman's resignation—became acting dean.