In celebration of Black History Month, the College features Dr. Tracie E. Bunton, who was the College’s first Black female veterinary graduate. She earned her doctor of veterinary medicine degree from the College in 1977. She then went on to complete a residency and earn her PhD in Comparative Pathology from the University of California at Davis, and is a diplomate of the American College of Veterinary Pathologists (DACVP). She also received an associate of applied science degree in fashion merchandising from Parsons School of Design (The New School), and is an accomplished artist who explores African American cultural identity and experience.

Bunton was recently featured by the Multicultural Veterinary Medical Association (MCVMA) and Black DVM Network in their project The First but Not the Last, which highlights stories of Black individuals in veterinary medicine.

What led you to your current career path?

I’ve been a preclinical consultant to the pharmaceutical industry since 2004, and founded my own company, Eicarte LLC in 2006. Although I practiced for a year after graduation from veterinary school, I knew I wanted to be a pathologist, so I did a residency/PhD program at UC Davis. I was faculty at MSU and Johns Hopkins for many years and then I joined the pharmaceutical industry in 1999. I believe that teaching is one of the most valuable things you can do in life, but I got burned out trying to pursue research funding for my lab. So, it was either join some giant research group at Hopkins, or leave. I left, and it was one of the best decisions ever. Academicians at the time were fed the myth that the pharmaceutical industry was for dullards solely in the pursuit of higher income. I found the exact opposite to be true. It has been extraordinarily challenging and interesting.

Although I’ve always continued to function as a pathologist, from the beginning at DuPont Pharma (my first pharma job), I was put onto a project team with major responsibilities in shepherding a new drug from early discovery through development. I didn’t know anything. So, I made it my goal to learn every aspect of the business. I remember purposefully joining meetings with the chemists to try to learn something—anything—because that was the most bewildering aspect to me. The chemists knew I was ignorant but trying, and so they helped me to figure things out. After DuPont and Purdue Pharma, I started consulting. All of my attention to the process of drug development—discovery, chemistry, pharmacokinetics, toxicology, pathology, and clinical—was worth it because you need to appreciate the whole picture to understand how you fit into it. Drug development is like looking down a dark road where there is potential for disaster at every corner. My job now is to help advise the decision-making process at each step.

In 1977, you became the first Black female veterinary graduate from MSU. What did that mean to you?

It meant a great deal to my parents. They were very proud, especially my mother. She talked it up quite a bit to everyone who would listen. For me though, the entire veterinary school experience was so intense, it was only a data point. I crammed all of the prerequisites into two years, and then entered the three-year program. Five years out of high school, I was a graduate veterinarian, feeling like I had been shot out of a canon.

After a while, you get used to being the only Black person in the room, although there is always, always an awareness that you better not mess up. Once I started going to American College of Veterinary Pathologists (ACVP) meetings, it was cool to meet the Black pathologists (early-on, it was mainly men), and gradually, more color started appearing, both men and women. Also, in the beginning, meeting the older women who were successful in the business was meaningful. I remember being in awe of those women. They had made it through.

Looking at the totality of my experience through a racial lens, I thought that by simply being my best—and I’m old enough to acknowledge that my best is very good—I could change minds. And maybe some did. But people have a remarkable ability to reconcile and/or discount reality so as to maintain their biases and prejudices and hate. If I succeeded as a Black person, it was handed to me. If I succeeded, I’m an anomaly, an outlier, an exception to their mental rules. I think that kind of reconciliation happens constantly in this society, and that is what we must break through. Change has occurred, and I hope in significant ways for young people of color aspiring to be veterinarians today. However, bearing witness to the events coming up to and through January 6, 2021 is enough to know things have changed, but not enough.

What advice would you give to current veterinary students or students interested in veterinary medicine as a career?

You need to love it. I am in great admiration and respect of veterinary pathology as a discipline to this day, even though I have functioned mainly as a regulatory toxicologist for many years, and eternally grateful for the solid education I received at MSU and UC Davis. Any other advice has to be more general because I’ve been away from veterinary students and veterinary medicine for too long to provide specific advice. What has worked for me is focus and hard work. And don’t make excuses. If there is a significant barrier, there may be five different ways around that won’t involve breaking your neck trying to go straight through it.

How has your MSU veterinary education shaped your life?

The three-year program was a beast, but it was a very strong, solid foundation from which I could continue my career path. I have tremendous appreciation for the discipline, dedication, and commitment of my classmates because we all just put our heads down and got on with it, with respect for one another, as a team. Those core values—discipline, commitment, and respect—instilled by my parents were solidified by those early experiences at MSU. Seeing the necessity of teamwork to achieve success was also extremely valuable.

What’s something you learned in vet school that you still use today?

Same as above. Discipline. Dedication. Commitment. Respect. Teamwork.

Who was your favorite professor and why?

Dr. Al Trapp. He knew everything. I remember the sly smile that he would have right after we asked some dumb question, but he never denigrated anyone. He was an excellent teacher.

What are your hobbies or interests outside of veterinary medicine?

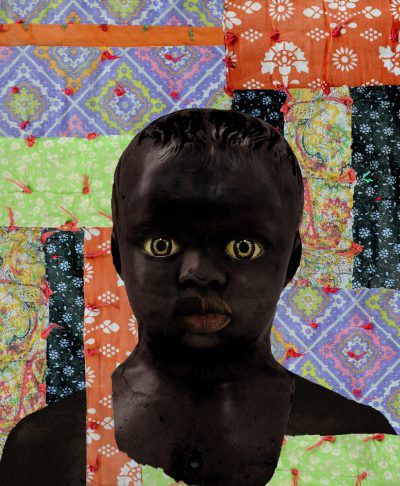

Making art that features the culture, history, and experiences of people of color. Studying the history of Black artists, most of whom I’d never heard of until recently. My dogs. My gardens.

What’s your favorite way to celebrate being a Spartan?

Not actually a celebration, but I do watch with interest and pride what comes across on LinkedIn related to MSU.