PhD candidate Andrea Minella, DVM, is one of the veterinary research scientists working in the Comparative Ophthalmology Lab with Dr. Simon Petersen-Jones.

A cat that cannot see loses some of the wonder of being a cat. He cannot watch the birds or chase his prey, be it an actual mouse or a toy. He cannot prance after a butterfly or leap from perch to perch. In the case of some eye diseases, current technology and treatments cannot give that sight back. But this may change for cats with an inherited eye disease called Progressive Retinal Atrophy, thanks to the discovery of a little secret being kept by bacteria.

Scientists discovered that bacteria use a collection of genetic sequences and an associated enzyme as part of their defense against invading organisms such as viruses. This system, called CRISPR-Cas9 (pronounced crisper-cass), remembers, recognizes, targets, and then cuts viral DNA, rendering them ineffective. Scientists then wondered whether we could harness this system to precisely target and cut DNA as a means of treating diseases caused by genetic mutations. Over the last nine years, CRSIPR-Cas9 has been engineered to do just that.

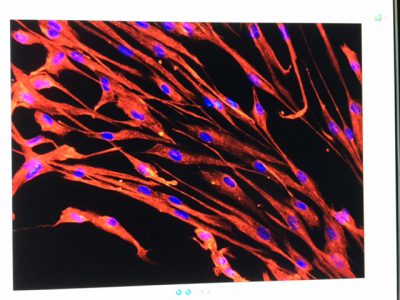

Our team of veterinary research scientists here at the MSU College of Veterinary Medicine are working toward using this system to edit the genetic defect in cats with a particular form of PRA. The concept is simple: direct the CRISPR-Cas9 system to cut out the mutated region of the implicated gene and replace it with a “normal” bit of DNA, thereby correcting the disease-causing mutation.

The execution, however, is far more complex and is still being developed at the cellular level. More laboratory work will need to be conducted before we can utilize the CRISPR-Cas9 system to edit the gene mutation in PRA cats, but that is what Dr. Simon Petersen-Jones and I are working on in the Comparative Ophthalmology Laboratory. We are optimistic this can be done. We also are optimistic that this could apply to humans.

The same gene that is mutated in cats with the main form of PRA, Cep290, is mutated in about 20% of children with the human form of the disease, known as Leber Congenital Amaurosis (LCA). Symptoms of LCA appear in infancy and the disease rapidly progresses to cause legal blindness. There is currently no treatment for this form of LCA, but if the CRISPR- Cas9 editing can successfully treat blindness in cats with Progressive Retinal Atrophy, this proof-of-concept data could be used to reach clinical trials in people.

As veterinarians conducting translational research, our findings can bridge the gap between veterinary and human medicine. In doing this, we can help the scientific world move forward toward better therapies for both people and their pets.