It is widely known that modern, institutionalized veterinary education began when Claude Bourgelat founded the Royal Veterinary School in 1761 in Lyon, France. But veterinary medicine itself began long before Claude got that open-‘er-up order from King Louis XV. In fact, research shows evidence of rudimentary practices and knowledge that date as far back as 9000 BCE.

Veterinary medicine during ancient times has never been the hot topic everyone is dying to research, and those who do undertake the task find it difficult; records from that far back in history are often incomplete, sometimes uncredited, and usually pieced together using multiple sources and translations from ancient Greek, Latin, Arabic, and other languages. Still, a rudimentary timeline has been developed.

Traditional Chinese veterinary medicine dates back to 10,000 years ago. According to legend, Emperor Fusi taught the existing primitive Chinese society how to domesticate animals. With domestication came the need to care for those animals, and so, Fusi founded animal husbandry and veterinary medicine in China. In Middle Eastern countries, shepherds used a “crude understanding” of basic medical techniques and skills to tend to their dogs and other animals.

During the Stone Age, ancient veterinarians used early forms of herbal medicine. Around the start of the Bronze Age (approximately 3000 BCE), a man named Urlugaledinna, who lived in the Mesopotamia region (modern day Syria, Iraq, Iran, Turkey, and Kuwait), was known to be an expert at healing animals. Urlugaledinna is sometimes given the title “father of veterinarians.”

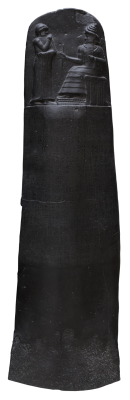

The ancient history of veterinary medicine also includes several familiar names; your middle school history teacher wants to know if you remember The Code of Hammurabi. Carved into a single, massive, black, stone pillar, The Code of Hammurabi is one of the earliest and most complete legal written codes. It was proclaimed by a Babylonian king named (what else?) Hammurabi, whose history of naming things after himself went from 1792 to 1750 BCE. In the Code, Hammurabi not only set out veterinary fees, but also fines for malpractice.

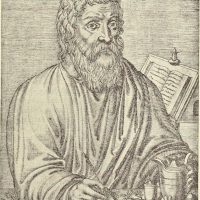

Jump ahead a thousand years or so, and more readily available written information makes the research a little easier. In comes Hippocrates, born in 460 BCE in the Grecian sunshine and widely regarded as the father of medicine (Hippocratic Oath, anyone?). Known for his role in taking the magic out of medicine, his work on humoral pathology and the assertion that “disease was the product of environmental factors, diet, and living habits, rather than a punishment inflicted by the gods” affected both veterinary and human medicine for 2,000 years.

Hippocrates’ ideas about how public health is connected to the environment are the earliest written evidence of what we now call One Health, a concept apparent even in ancient times. As veterinary medicine and education continue progressing into the future, and embrace this interdisciplinary approach, it’s exciting to trace the history of veterinary medicine back to the roots of civilization.

In the midst of missing texts, sketchy recorded history, and translations from ancient languages, one thing is clear: even when people were writing books on papyrus, the connection between caring for humans, animals, and the environment was unmistakable.