The unexplained death of a horse in Ohio launched an investigation that has now linked a fatal disease with a virus never before known to cause illness.

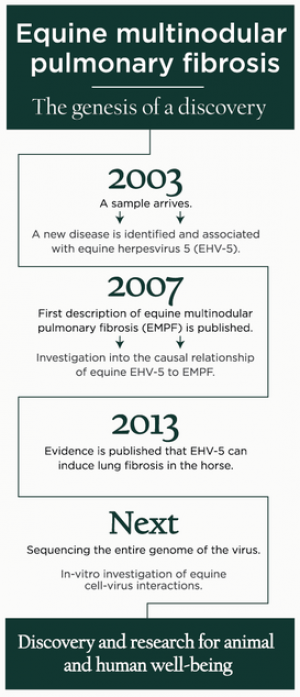

In 2003, Cindy Jackson, DVM, performed a necropsy on a horse in Ohio that died of unknown causes.

The clinical signs—progressively worsening respiratory disease and weight loss—and her finding firm nodules throughout the lungs at the time of necropsy, were perplexing so she contacted MSU pathologist Kurt Williams, DVM, PhD, DACVP, to discuss sending a sample of the lung tissue to him.

The initial evaluation failed to identify a cause for the remarkable lung disease. Over the next months, Williams and colleagues identified equine herpesvirus 5 (EHV-5) associated with this initial case and subsequent additional case material sent to the Diagnostic Center for Population and Animal Health. What began as an interesting diagnostic challenge has now grown into a research project that has led to the identification of a new and important equine pulmonary disease and its association with EHV-5.

In 2008, Williams, associate professor in the Department of Pathobiology and Diagnostic Investigation, published the first description of this disease, which he named Equine Multinodular Pulmonary Fibrosis (EMPF). EMPF is a spontaneous lung disease characterized by inflammation and scarring of the lungs. The scarring causes loss of lung function and an inability of the horse to get enough oxygen. EMPF is progressive and usually responds poorly to therapy, thus it is often fatal for the affected horses.

This fibrosing lung disease in horses has a clinical corollary in humans—idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). IPF, like EMPF, is characterized by progressive scarring of the lungs that causes loss of the tissue’s ability to transport oxygen and makes it increasingly difficult for a person to breathe. This is often described as a feeling of suffocation or an intense tightening in the chest.

Approximately 128,000 Americans suffer from IPF, and each year the disease claims the lives of more than 40,000 people—about the same as breast cancer. Few people have heard of IPF, but it is five times more common than cystic fibrosis and Lou Gehrig’s disease. There is no cure and the survival time is usually less than five years after diagnosis. The cause of IPF is unknown, but is thought to result from a combination of factors that cause injury to the lung, including possibly viruses such as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV).

“The virus associated with the EMPF in horses is a gammaherpesvirus. This is the same type of virus as EBV, which has received attention as a possible trigger for IPF in humans,” Williams says, “so finding this disease in horses may be important in determining whether a gammaherpesvirus can induce pulmonary fibrosis. This is an important question to address to better understand fibrotic lung diseases overall.”

Can a virus do it?

After Williams’s team identified the disease in horses—and the association of the disease with EHV-5—the next question to ask was whether the virus was the cause of EMPF.

Working with Williams in this subsequent study were several researchers involved in the identification of EMPF, including Steven Bolin, DVM, PhD, and Roger Maes, DVM, PhD, from the Department of Pathobiology and Diagnostic Investigation, and Edward Robinson, BVetMed, PhD, from Large Animal Clinical Sciences.

“In the 2008 study we associated the presence of EHV-5 in the lungs of horses with the presence of EMPF—but that doesn’t prove a causal relationship,” Bolin says. “There had not been any attempt to reproduce EMPF, to induce the disease. That was what we set out to do.”

And that was what the team did. They published a study in 2013 that provides strong evidence that EHV-5 is the cause of EMPF.

This is the first example of a gammaherpesvirus inducing lung fibrosis in the natural host species without additional known lung injury. Additionally, their data suggest that gammaherpesvirus infections may initially elicit lung injury during a latent phase of viral infection, and may elude detection using standard laboratory techniques.

“We now know that a gammaherpesvirus can induce lung fibrosis in the natural host, and we hypothesize that induction of fibrosis happens while the virus is latent,” says Williams. “Our findings also suggest that not all EHV-5 is pathogenic, but rather that a few strains of the virus are capable of inducing lung fibrosis. These findings have important implications when considering detection of gammaherpesvirus in the lungs of humans with pulmonary fibrosis.”

Next steps:

Gene sequencing and in vitro study

One of the team’s next steps is to sequence the entire genome of the virus associated with EMPF to compare to the genome of variants of the virus that are commonly found in clinically normal horses.

The team will also sequence samples of EHV-5 sent to them from Iceland, where the horse population has been isolated for at least a thousand years. Icelandic horses do have EHV-5, but the disease has not been reported there. Sequencing the Icelandic virus genome—which should be what Williams calls “a pristine virus”—is a way to investigate old and new pathogens.

“We suspect we’ll find evidence that the virus samples recovered from horses with the disease will have differences within their genomes compared with the genomes of the non-pathogenic forms of the virus found in clinically healthy horses,” Williams said. “We hypothesize that the virus associated with EMPF has picked up a gene(s) that lends pathogenicity to it.”

The second effort the team will undertake is in-vitro investigation of the biology of equine cell-virus interactions. Williams has begun work with Gisela Hussey, DVM, MS, PhD, assistant professor in the Department of Pathobiology and Diagnostic Investigation. Hussey investigates equine herpesvirus type 1 (EHV-1), including immune responses to EHV-1 in the cells lining the equine respiratory system.

Studying the biology of the virus, not just the genome, may help answer some important questions that relate to how the virus might be causing disease within the lungs of affected horses.

Collaboration for a cure

Williams’ efforts investigating EMPF, as well as his work investigating other similar diseases in other veterinary species, has spurred a collaborative effort between human medical and veterinary clinicians and researchers.

Williams has worked with Jesse Roman, MD, and other researchers to organize the Fibrosis Across Species meeting to be held the last week of April 2014. The meeting will be held at the University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky, where Roman, a pulmonary fibrosis and interstitial lung disease researcher and clinician, chairs the Department of Medicine.

“This meeting will create opportunities for collaboration between human and veterinary medicine,” Williams said. “They’re gathering together an impressive team of scientists. I am pleased to be part of this group and this meeting, where we hope to move forward with collaborative research projects that promise to benefit both human and veterinary patients in the future.”

Posted: Spring 2014

Contact: Casey Williamson