By Dr. Ashley VanderBroek, faculty for the MSU Equine Surgery Service

Featuring Dr. Lindsay Knott, resident for the MSU Equine Surgery Service; Dr. Julie Strachota, faculty for the MSU Equine Theriogenology Service; and Brandon Frantz, fourth-year DVM student

History and Presentation

Strong Impulse (Jack), a seven-month-old homebred Quarter Horse colt, was presented to the MSU Equine Surgery Service in September 2020 for laparoscopic (minimally invasive) cryptorchidectomy (removal of a non-descended testicle). Jack was previously anesthetized on the farm in July for a routine field castration. When the right testicle could not be palpated, surgery was not attempted and Jack was recovered. He was then brought to his primary care veterinarian’s clinic for conventional cryptorchidectomy. An open inguinal approach to the abdomen was made, but the right testicle was still unable to be located. His left testicle was descended into the scrotum but was not removed. Jack was referred to MSU for laparoscopic cryptorchidectomy.

At the time of presentation at MSU, Jack was bright, alert, and responsive. His mucous membranes were pink and moist with a normal capillary refill time. No abnormalities were identified on cardiovascular and gastrointestinal auscultation, and digital pulses were within normal limits. Jack’s left testicle was descended into the scrotum, but the right testicle could not be palpated. A complete blood count and limited serum chemistry revealed no abnormalities.

Diagnosis

Because Jack’s right testicle had not descended into the scrotum, he was diagnosed with cryptorchidism. It was assumed that the right testicle was retained within the abdomen and Jack was prepared for laparoscopic surgery to locate and remove the testicle.

Treatment and Outcome

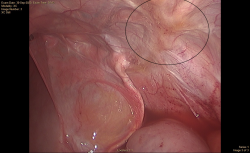

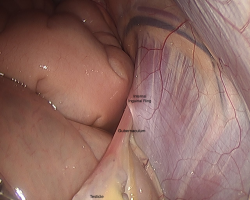

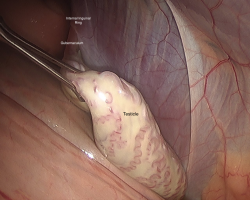

Jack was anesthetized and positioned in dorsal recumbency. A scar was present over the right inguinal region from the previous attempt to locate the testicle. The ventral abdomen was clipped and aseptically prepared for surgery. The abdomen was explored laparoscopically, but the right testicle was not identified. The left internal inguinal ring appeared normal in appearance with the spermatic cord traversing the canal as expected (Figure 1). However, the right internal inguinal ring was obliterated by fibrosis (scar tissue) with no visible gubernaculum (Figure 2). The gubernaculum is the structure that is responsible for testicular descent and connects the testicle to the scrotum (Figure 3).

After extensive searching of the ventral abdomen, the procedure was converted to a conventional right parainguinal open approach. Despite manual palpation of the dorsal abdomen, the team was still unable to identify the right testicle. After contacting the owner and discussing the options, it was decided to pursue hemi-castration and delayed hormonal testing. The left testicle was removed using a modified open inguinal approach and all incisions were closed primarily. Jack recovered well from general anesthesia and remained comfortable postoperatively. He was discharged the following day with instructions to pursue hormonal testing 30 days later. In November 2020, baseline testosterone levels and hCG stimulation indicated no functioning testicular tissue. These hormonal results indicated that Jack was, in fact, a gelding, despite only having one testicle removed.

Comments

Cryptorchidism is defined as the failure of one or both testicles to descend into the scrotum. This condition is not uncommon in horses, and the retained testicle is usually located within the abdomen or inguinal canal. Monorchidism, or the condition of only having one testicle, is extremely rare in horses. It is thought to occur due to either testicular aplasia (failure to develop) or idiopathic infarction (loss of blood supply), but these are speculative due to the rare occurrence.

Since cryptorchidism is fairly common, but monorchidism is not, we teach students to always assume that there are two testicles. Removal of only the descended testicle will cause the horse to externally appear like a gelding, but the retained testicular tissue still produces testosterone and leads to stallion behavior. This can result in safety concerns for both humans and other horses. Because of this, we also teach students that the descended testicle should not be removed before the retained testicle.

In Jack’s case, the right testicle was not located, despite extensive searching using both laparoscopic and conventional approaches. Since the descended testicle was hormonally active, testosterone testing would not be helpful in identifying the presence of retained testicular tissue until after the descended testicle was removed. After discussing the situation with the owner, we pursued a left hemi-castration with the understanding that hormonal testing must be performed after one month to determine if Jack had any residual testicular tissue. The owners were instructed to handle Jack like a colt until hormonal testing confirmed whether or not he was, in fact, a gelding. If the hormonal values had been consistent with functional testicular tissue, additional investigation would have been necessary to locate the retained testicle. Thankfully, that was not needed, and Jack turned out to be one of the very rare cases that only had one testicle, to begin with.