History and Diagnosis

Sugar, a 4.5-month-old intact female Labrador Retriever, had dribbled urine her entire life. Sugar’s owners initially thought this was a behavioral issue. However, she could still posture and urinate normally when outside, and it became apparent that Sugar was unaware of her urine leaking. The incontinence was frequent, occurring both while sleeping and awake. Also of concern, Sugar developed urinary tract infections. Her veterinarian treated the infection with antibiotics, but unfortunately, antibiotic treatment did not improve her urinary incontinence. Therapy with phenylpropanolamine, an oral medication used to tighten the urethral sphincter, was attempted without success. At this point, Sugar was referred to the MSU Veterinary Medical Center for further evaluation.

Other than urine staining observed on Sugar’s perineal region and caudoventral abdomen, physical examination was normal. Additionally, she intermittently dribbled urine during the exam. Routine bloodwork and urinalysis were normal. An ultrasound was performed to assess Sugar’s urinary system. Her kidneys and bladder had normal architecture and were normal in size.

A dose of the diuretic furosemide was then given to aid in identification of the ureters and ureteral openings, which are often difficult to visualize during routine ultrasonography. Following furosemide administration, one of Sugar’s ureters was noted to enter the bladder wall in a normal location, but then tunnel beyond the pelvic canal. Sugar’s history and ultrasound findings increased suspicion for an ectopic ureter.

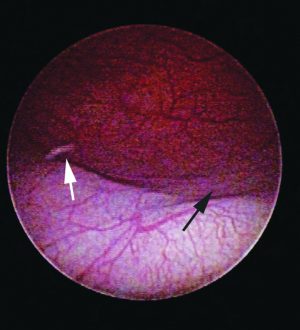

Sugar was placed under general anesthesia for urethrocystoscopic examination using a rigid 2.7 mm cystoscope. Her vestibule was mildly inflamed and had several prominent lymphoid follicles, consistent with her history of previous urinary tract infections. A thin paramesonephric remnant was present at the vestibulovaginal junction. Her right ureteral opening was located in the trigone region of the bladder. However, no orifices for the left ureter could be identified within the bladder lumen. Evaluation of the urethra revealed that the left ureter was ectopic with two orifices, both of which were located along the dorsal urethral wall. The diagnosis of ureteral ectopia was consistent with Sugar’s lifelong history of urinary incontinence that was non-responsive to medical therapy.

Treatment and Outcome

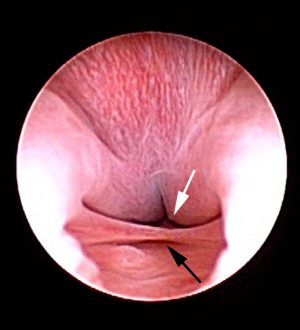

At the time of urethrocystoscopy, the left-sided ectopic ureter was catheterized by advancing an open-ended ureteral catheter over a hydrophilic-tip guidewire. Under cystoscopic guidance, a Holmium: YAG laser was used to carefully cut the ventromedial wall of the ectopic ureter. The ureteral opening was gradually moved from the distal urethra, across the proximal urethra, and into the bladder trigone. Sugar recovered from anesthesia uneventfully, and for the first time in her life, she was continent. Sugar was discharged from the hospital later that evening to her very excited owners. One year later, Sugar is still doing great with no evidence of urinary incontinence.

Comments

Ectopic ureters are an uncommon congenital anomaly in which the ureteral orifice is abnormally positioned, most commonly emptying into the urethra. Although an uncommon cause of incontinence in all dogs, it is estimated to be responsible for up to 50% of cases of urinary incontinence in juvenile female dogs. Male dogs can be affected as well, but less commonly. More than 95% of ectopic ureters are classified as intramural, in which the ureter enters the bladder in a relatively normal position, but then tunnels through the bladder and urethral walls prior to termination. The constant or intermittent urine leakage in these dogs often leads to development of urinary tract infections. Other concurrent congenital abnormalities, such as urethral sphincter mechanism incompetence, hydroureter, renal dysplasia, and paramesonephric remnants, are common. Many of these dogs are relinquished to shelters or euthanized because of the severity of urinary incontinence.

Although surgical correction is a viable option for these cases, cystoscopic-assisted laser ablation offers several advantages for the treatment of intramural ectopic ureters. First, diagnosis can be confirmed at the same time that a therapeutic intervention is performed. This is clearly beneficial as it only requires one procedure for both diagnosis and correction. Additionally, surgical correction requires not only an abdominal incision, but also incisions into the bladder, urethra, and ureter. As such, cystoscopic-assisted laser ablation is less invasive and associated with quicker recovery times. Regardless of treatment technique, some of these dogs remain incontinent due to concurrent urethral sphincter mechanism incompetence, but many of these cases can be successfully managed with oral medications. Overall, owner satisfaction with cystoscopic-assisted laser ablation of ectopic ureters is excellent.