Read More

Read More

Surgeon, scientist, inventor, and mentor, Dr. Loïc M. Déjardin came to the United States from France in 1989 as the MSU College of Veterinary Medicine’s first International Surgical Fellow. He then studied under Dr. Terry Braden as a surgery resident and earned his master’s in comparative orthopedic research under Dr. Steven Arnoczky’s mentorship. Now professor and head of orthopedic surgery in the Department of Small Animal Clinical Sciences, he honors the legacy of Wade O. Brinker through his creativity in research and his commitment to pushing the limits of orthopedic surgery.

“Loyalty is the key word in mentorship. You have to have absolute loyalty both ways.”

As an orthopedic surgeon, Déjardin has contributed to an international paradigm shift in approaches to surgical fracture repair. His research activities on biomechanics and implant design led to the development and refinement of techniques for minimally invasive surgery and the invention of an intramedullary nail used for the treatment of long-bone fractures.

Déjardin credits his professional success to his eclectic training under Steven Arnoczky and Terry Braden, as well as the influence of Gretchen Flo, Charles DeCamp, and Wade O. Brinker, who is regarded as the father of veterinary orthopedics.

“Wade Brinker was known for his patience, creative thinking, and pioneer spirit,” Déjardin said. “He held himself to the highest standards and expected the same of his students and the profession in general. As orthopedic surgeons, we are all influenced by his philosophy.”

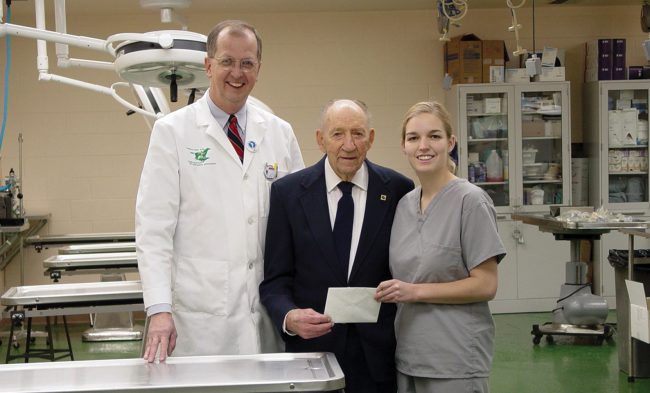

On several occasions during his residency, Déjardin had the unique opportunity to operate with Brinker, who had retired long before. Déjardin and Brinker performed a fracture repair together that ended up being the last procedure that Brinker performed at MSU. Déjardin has fond memories of these special moments, and considers it a true privilege to share Brinker’s wisdom. Brinker’s teaching was instrumental in shaping Déjardin’s view of veterinary orthopedics and had a tremendous influence on his evolution as a trauma surgeon.

Key Mentorship

One of Déjardin’s influential mentors, Gretchen Flo, was Brinker’s protégé. Throughout Déjardin’s time at MSU, she has played a key role in his career.

“Gretchen Flo has been and remains an irreplaceable mentor to me—beyond orthopedics, on a personal level,” said Déjardin. “Flo is a life mentor and a life coach, who has been essential to my success. From the onset of my tenure at MSU, Flo and I developed a special personal bond, which I suspect may have led to Brinker’s sustained interest in my development. He regularly inquired how I was doing, what I was doing, how I was progressing.”

Terry Braden was Déjardin’s clinical mentor.

“Braden was an outstanding orthopedic surgeon,” Déjardin said. “He was far ahead of his time in terms of soft tissue handling. He was a remarkable minimally invasive trauma surgeon before this approach to fracture treatment was embraced by the orthopedic community.”

Arnoczky, too, was an important mentor. He provided the research mentorship that helped shape Déjardin as the clinical scientist he is today. He guided Déjardin through the rigors of the scientific process, demonstrated how to develop well-structured investigative methods, and taught him how to conduct objective analyses of research results.

“What always fascinated me in Arno’s work was his uncanny ability to see what others did not,” said Déjardin. “People look at challenges but do not necessarily see and analyze problems the way he is able to. This is not an entirely natural process, however, it reflects discipline, requires relentless attention to details, critical thinking, and intellectual flexibility. Arnoczky just makes it appear easy, it is anything but!”

Applied Science

Product Development and Industry Collaboration

“You have to drop your ego a notch to collaborate with people. I have a reputation for being someone with strong, unflinching opinions, it is quite the opposite actually. Present a logical, well-structured compelling argument and I will have no problem changing directions.

“Teamwork is critical to any meaningful achievement, and giving credit to everyone who contributes is a requirement for myself and my team. Working alone is a direct path to failure. Developing the I-Loc™ nail was successful because of the complementary competencies and shared work of residents, research associates, fellows, and graduate students. The input of engineers from Dr. Haut’s laboratory was essential. Having a leadership role is certainly important, yet it is not much without a team dedicated to the success of an idea.

“You also have to be passionate and believe in your idea. How can you convince industry partners to follow you and foundations to financially support your research otherwise? Making something like this happen demands that you coordinate the work of people with such diverse academic backgrounds, from medicine to engineering, industry, foundations, even IP lawyers. This is where and how you learn to listen to other peoples’ ideas, collaborate, and compromise. Mutual respect, trust, strong partnership at different levels are vital to what we do.”

Déjardin credits Arnoczky for teaching him an incremental approach to science. More than having a vision, an ultimate goal, it is essential to approach any challenge in a structured, step-by-step fashion. Addressing each component of a problem is easier, less frustrating, and far more effective than tackling the entire issue at once. Importantly, one must keep an open mind and be ready to change direction during this process, which can be quite an ego bruiser.

“Where Arno and I differ is that he can be a more abstract basic science researcher than me,” Déjardin said. “Yet he has the ability to see the clinical implications of his fundamental research. Indeed, a lot of his work has had major clinical impact in both human and veterinary orthopedics.”

Déjardin sees himself as a pragmatic applied science researcher. He likes to identify clinical challenges and propose a multifaceted approach to revolving them through the development of new surgical techniques, more effective implants, or surgical instrumentation. Yet Déjardin also understands that these refinements must be tested in the lab prior to implementation. This “bench-to-trench” approach has served as the foundation of his research program at MSU.

Among Déjardin’s most significant contributions to veterinary orthopedics are the creation of a comprehensive minimally invasive osteosynthesis (MIO) program, the development of an interlocking nail used in MIO, the I-Loc™ intramedullary nail, and the ongoing promotion of robotics in orthopedic surgery.

Minimally Invasive Osteosynthesis

The fundamental tenet of surgical fracture repair is the optimization of the patient’s functional recovery following trauma, in large part through hastening fracture union and decreasing complication rates.

Déjardin’s long-lasting involvement with the AO Foundation has been central to the development of MIO programs at MSU and abroad. The AO Foundation, the largest orthopedic foundation in the world, is composed of four specialty divisions: TRAUMA, SPINE, CMF, and VET. AO is fully dedicated to the education of surgeons in operative principles aimed at improving fracture treatment.

Through his involvement with AO, Déjardin encountered another pivotal mentor, Jean-Pierre Cabassu, previous chairman of AOVET and currently member of the AO Foundation Board. Cabassu shared his enthusiasm and experience with MIO as it was becoming the standard of care in human medicine. Déjardin saw its potential for small animal orthopedics, became part of AO’s international movement that emphasized the preservation of the biologic environment of the fracture, and began his investigations and advancements of the method.

Déjardin currently serves as a trustee of the AO Foundation, as well as faculty at advanced orthopedic courses taught worldwide. He developed and leads a wide-ranging minimally invasive orthopedic traumatology course that teaches cutting-edge surgical techniques that he developed at MSU.

Déjardin’s team helped develop a new philosophical approach to surgery using MIO in veterinary medicine. This approach uses indirect techniques, is less likely to disrupt the vital blood supply to the bone, and promotes more rapid healing. One of the implants used in MIO is the I-Loc™ interlocking nail that Déjardin designed at MSU.

I-Loc™ Nail

The surgical fixation of long-bone fractures with interlocking nails has been the gold standard in people. Unfortunately, in dogs, standard interlocking nails provided inadequate stability.

To remedy the standard nail’s shortcomings, Déjardin invented the I-Loc™ interlocking nail, which through an improved locking mechanism and nail profile is currently the only intramedullary fixator used in both human and veterinary orthopedics. This implant provided a significant contribution to the MIO philosophy. The versatility of I-Loc™ increased the variety of fracture types that could be successfully repaired with interlocking nails, and for the first time, allowed for corrections of challenging angular deformities and revisions of failed plate osteosynthesis.

Developing the device was a collaborative project involving researchers, investors, and industry partners. Such endeavor required commitment and perseverance, frank communication, and compromise, as well as open-mindedness, and yet confidence in the soundness of the original concept.

“This is a grueling, yet exhilarating process, a roller coaster ride between failures and “Eureka” moments, a true lesson in humility,” Déjardin said. “Validating your proof of concept is a major early energy boost as you know it can lead to clinical applications that would benefit our patients. Yet it is not much until you have a final, fully functional product in your hands.”

One of the prerequisites of the I-Loc™ development was full compatibility with the MIO surgical philosophy and program.

“While we may not be able to formulate a detailed plan from the onset of a project, you know the seed of the final idea is there,” said Déjardin. “Having a larger plan and keeping your eyes on your ultimate goal are essential as you start putting a program together. With the successful completion of each, seemingly unconnected step, the coherence and comprehensiveness of your plan becomes more apparent. Then only you realize that the end product, the ultimate reward, is within reach.”

Déjardin as a Mentor

The future of our profession rests in large part on the formation of younger generations of veterinarians, who will be inspired to make life-long contributions to their chosen fields, whether as clinicians or researchers. We don’t just stumble upon great students. It takes time, commitment, and dedication to scout, then recruit promising students, yet more time to train residents to become proficient in surgery and in research. This vital task takes time and effort. Déjardin considers ten years an adequate time to train a young clinician scientist.

“Throughout my career, I have been fortunate and privileged to cross paths with powerful, inspiring mentors,” Déjardin said. “My commitment to mentorship stems from an acute awareness of

the benefit of working with nurturing, though provoking peers, and a deep sense that it is my responsibility to pay it forward. Having a sense of belonging to a lineage of great surgeons is awe inspiring. I only hope I can humbly share this legacy with younger generations.”

Throughout his tenure at MSU, Déjardin has been a strong advocate for international collaboration and, in line with MSU’s outreach mission, for the recruitment of international young talent. In the mid-2000s, Laurent Guiot and Reunan Guillou completed their surgical residencies with Déjardin and then stayed on as faculty for several years. During this eight-year span, Déjardin trained them in surgery and research with the intent of grooming them for academic careers. Now successful faculty members at The Ohio State University, both have already made significant contributions to the field and have established a strong national and international presence.

“You recruit them when they are puppies,” Déjardin likes to affectuously say of his mentees. “Your job is to nurture their growth, guide them to fully express their own potential, teach them how to avoid mistakes, steepen their learning curve as much as possible, channel their ambition.” Importantly, as a mentor, you do not want to create clones of yourself. Quite the opposite actually, you want to promote diversity, nurture creative innovations, and stimulate the formulation of daring ideas. Being a mentor also means that you must have your mentee’s best interest in mind. You must want them to surpass your own accomplishments, in time. Their success is your reward, and a potent motivator. Their struggle is yours as well.”

“MSU undeniably leaves a mark on people. You stop by MSU and it’s going to leave a mark on your way of addressing problems, your professional career, and possibly your way of life. This is very telling of the quality of the training that we provide.”

Déjardin is working to build the next generation of MSU orthopedic faculty. The recent recruitment of Dr. Karen Perry and Dr. Sun Young Kim is an essential component of his long-haul plan. Their commitment to self-improvement, team-building mentality, and complementary strengths are important to Déjardin, who considers their recruitment as an accomplishment.

Perry and Kim each made the choice to come to MSU and work with Déjardin. Perry came from the Royal Veterinary College in London, UK, and Kim joined MSU from the University of California at Davis.

While certain that MSU’s clients and students will benefit from Perry’s and Kim’s expertise as surgeons and educators, Déjardin is equally confident that they will grow during their time at MSU.

“MSU undeniably leaves a mark on people,” said Déjardin. “You stop by MSU and it’s going to leave a mark on your way of thinking, your way of addressing problems, your professional career and possibly your way of life. This is very telling of the quality of the training that we provide.”

With Perry and Kim on board, Déjardin is building a cohesive, diverse clinical and research team. Excellent surgical aptitudes and proficiency in clinical and theoretical research, as well as impeccable teaching and pedagogic skills, are some of the qualities that Perry and Kim are contributing to MSU.

“Creating a critical mass of like-minded skilled individuals is difficult to achieve,” said Déjardin. “We are very lucky to have these two young talented faculty here.”