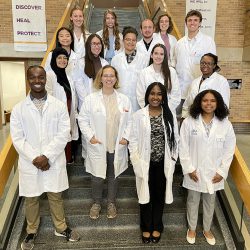

Although since 2009 women veterinarians have outnumbered their male counterparts, there are still challenges in attaining equity in the field. In honor of March being Women's History Month, we spoke with women from the MSU College of Veterinary Medicine about their thoughts and role models.

Taylor Epp, director of the Veterinary Nursing Program

About: Taylor loves sharing her passion for veterinary medicine and for learning with future professionals by creating an environment where students can discover and develop their individual passions. Taylor graduated from MSU’s Veterinary Nursing Program (then the Veterinary Technology Program) and is a licensed veterinary technologist. Taylor practiced as a surgical oncology nurse for several years before moving into academia to instruct in the Veterinary Nursing Program. Taylor received her master’s degree in educational technology from Michigan State University and moved into the director role in 2017, where she leads a faculty of highly dedicated instructors and gets to engage with a group of very motivated veterinary nursing students.

Who is the woman who has influenced you the most over your lifetime? “Choosing just one is a difficult task. I have had the pleasure to learn from and work with some pretty amazing women. However, the title of “most influential woman in my life” has to go to my mother. Growing up, I watched her raise my two brothers and me as a single parent after my father passed away, selflessly putting all of herself into our family to ensure we had everything we needed. As a parent, she set high standards and expected that her children always put forth their maximum effort, and she was compassionate and caring and always there to pick us up when we failed—helping us find the confidence to try again. That expectation has motivated me to take chances in life, and that compassion allowed me to see failure as an educational experience instead of the end of a road.

As a schoolteacher, she worked hard to make each day meaningful for her students and to help them find successes every day, even if they were small. Her work ethic and desire to make a difference in each child’s journey was a constant in the background of my upbringing. Her dedication, flexibility, and curiosity urged me to explore and understand educational accessibility and how impactful a passionate teacher can be in a student’s life.

My mother’s influence has shaped who I am as a mother, teacher, wife, and friend.”

How can the veterinary community be more supportive and inclusive of women? “Although women outnumber men in the profession and it may seem that this statistic proves equality, women in veterinary medicine still face sexism, misogyny, and inequality regularly. The American Association of Veterinary Colleges states, “Veterinary medical environments are gender equitable when every person in the profession can reach their full potential and no one is disadvantaged because of their sex and/or gender expression.” It starts with us in the College, and the environment we create for the preparation and growth of our veterinary professionals. We must be dedicated to creating diverse, equitable, and inclusive veterinary learning environments for all students. We need to be diligent in generating gender-inclusive and equitable policies and practices—and removing any that are gender exclusionary and/or marginalizing. The College is committed to creating a gender equitable environment and I am encouraged by changes we have seen over the past years.

I also believe we should normalize the fact that a career may not end up looking as it was initially planned. There is an immense amount of pressure on students to follow through with their sometimes super-specific goal of becoming a certain type of practicing veterinarian or veterinary nurse. There is a feeling that this goal is what they must be, and all they can be. However, most professionals will tell you that they didn’t take a straight path to where they are now, and due to opportunities presented, plans that didn’t pan out, or unrelated life choices, they have ended up where they are today. And that’s okay. It’s great in fact! Each turn in the road is a chance to learn and grow, and although to a student or new graduate with a clear idea of what their path needs to be, a twisty bumpy road may seem scary and can be misinterpreted as a failure, it’s actually the path most traveled and will lead you to where you are meant to be (even if that is not where you initially planned to be). I was recently reminded how remarkable the field of veterinary medicine is in the variety of ways a veterinary nursing and DVM graduate can use their degree in the world. Encouraging students to be open and stay open to challenges that are presented to them may allow our women and all students to embrace the uncertainty as opportunity.”

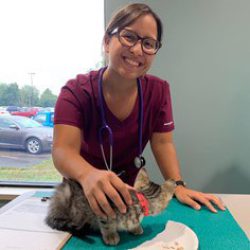

Kimberly Guzmán, Doctor of Veterinary Medicine Class of 2023

About: “My name is Kimberly Guzmán, but many people call me Kimmy. I am a first-generation, Ecuadorian-American, third-year, veterinary medical student. My parents left Ecuador and moved to New York City for a better life for them and their three children. Eventually, our family moved to New Jersey. I attended Rutgers University in Newark, New Jersey and obtained a Bachelor of Arts and Sciences. I have focused my veterinary studies in the field of zoological medicine and companion animal medicine. I wish to become a veterinary clinician, researcher, and mentor. I am the current vice president of the DVM Class of 2023. I am very passionate about diversity, equity, and inclusion in the veterinary medical field. I am the co-founder and former president of the MSU College of Veterinary Medicine’s Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC) Club and current vice president of the College’s Veterinarians as One Inclusive Community for Empowerment (VOICE) Club. I hope to continue growing as a woman of color in veterinary medicine and am very excited for my clinical year, with externships scheduled at the Oregon Zoo, the Wildlife Center of Virginia, the Smithsonian National Zoo, and a research field trip to the Galápagos Islands, Ecuador.”

Who is the woman who has influenced you the most over your lifetime? “The woman that has influenced me the most throughout my lifetime is my mami (mom), Amparo! She is an Ecuadorian immigrant that came to this country without knowing any English. While my father worked several jobs to support our family, my mom cared for three children. While I was learning English grammar, she was learning it beside me. We spent hours going through flashcards and using translating devices to understand the most basic sentences. She struggled alongside us and taught us the importance of education. She encouraged me to be inquisitive about my interests and to seek answers no matter the obstacles. Despite having a modest budget, she planned exciting adventures for three kids in the big city. We rode the subway to different playgrounds around our neighborhood and on particularly special occasions we went to the American Museum of Natural History, the Central Park Zoo, and the Bronx Zoo. These adventures, immersed in animal science, sparked my curiosity and interest in a career as a scientist. After my siblings and I grew up, she studied and obtained a medical assistant certification and returned to the workforce. The woman that struggled with basic flash cards is now fluently bilingual and continues to inspire me to grow and improve myself. Amparo is a marvelous woman that I am blessed to call my mami and cooks the best seco de pollo (chicken stew).”

How can the veterinary community be more supportive and inclusive of women? “Throughout American history, men have outnumbered women in most medical fields. According to the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA), it wasn’t until 1910 that Dr. Florence Kimball and Dr. Elinor McGrath, became the first American women to receive a Doctor of Veterinary Medicine degree. The profession grew amongst women and in 2009 women veterinarians outnumbered male veterinarians 44,802 to 43,196. The veterinary community has come a long way in inclusivity for women. However, even after the increase of women veterinarians, women are often paid less than their male counterparts, according to a study in the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association.

In addition, the veterinary community is still in need of more women in veterinary leadership positions. For example, the AVMA has never had a woman president. This year, there are finally two women competing for this role. According to the American Association of Veterinary Medical Colleges, the majority of deans in American and Canadian veterinary schools are Caucasian men. Furthermore, according to the AVMA, the majority of veterinary practice owners in the United States are also men. The first steps towards being more supportive and inclusive of women would be by having clear, well-defined codes of conduct within a professional environment, including anti-discrimination policies and training programs addressing sexism and misogyny. These codes of conduct should also dictate the proper channels for reporting instances of sexist and misogynistic behavior. Practice owners must be more flexible to veterinarians raising children and returning to the workforce after years of raising children. A training program for returning practitioners, such as Smooth Operating Vets, can help create mother-friendly vet practices.

We must also acknowledge that some of the issues women of color face are different than white women. The lack of veterinary schools in the United States, low acceptance rate, and the cost of attending a school that may be far from home all contribute to women of color being underrepresented in the field. More outreach to racially and ethnically underrepresented groups of women is important. Having women role models can help young leaders grow, even more if they look like them and can relate to their backgrounds. I am a huge advocate of mentorship, especially pipeline development for underrepresented professionals. Veterinary schools and professionals should reach out to high schools and universities in states without veterinary schools to encourage. As a student at the College, I continue to help Micaela Flores with outreach events to help inspire students to join the veterinary field.

We must start/continue having conversations on how to help not only women, but women of color be successful. We must help encourage and promote strong and confident women. We must address internalized sexism. Addressing these issues can be tough but is vital to promote equality.”

Colette Zulu, research administrator

About: Colette Grace Zulu received a business computing certificate from Malawi College of Accountancy, and an advanced accounting diploma from the City and Guilds of London Institute. She held various accounting and data processing positions in the private sector in Malawi, before moving to the United States to pursue other opportunities. Colette attained a bachelor’s degree in international business and management from Northwood University, Midland, Michigan in 2010. She worked in the financial services, providing accounting support for Lansing Community College (LCC) and the LCC Foundation, before moving to MSU, where she has held various positions across campus. She is currently a research administrator in the Office of Research Facilitation at the College of Veterinary Medicine, providing professional support to the College’s researchers.

Who is the woman who has influenced you the most over your lifetime? “My maternal grandmother has been the greatest influence in my life. Although she did not have a formal education, she was street smart and she encouraged her daughters and granddaughters to value education, to work hard, and to aim high. Having grown up in a predominantly patrilineal society, she advocated for women to make choices that would lead to their independence.

My grandmother taught us family values, taught us to cherish family, to work hard, to see the good in others. She was the bedrock of her clan, and along with my mother, she shaped me into the person I am today. There are other women that have influenced my life as well, such as my teachers, supervisors, girlfriends, and sisters—but my grandmother tops the list.”

How can the veterinary community be more supportive and inclusive of women? “The number of female veterinarians has in recent years surely surpassed that of male counterparts, yet vestiges of women’s marginalization remain. For instance, the gender pay gap persists as women veterinarians still earn less than their male counterparts, according to a 2019 report by the U.S. Department of Labor and Statistics.

There is need for more advocates to be on the forefront to fight for the narrowing of this pay gap, in addition to the American Veterinary Medical Association and the American Association of Veterinary Medical Colleges, who continue to champion this cause.

Further, I think that it is necessary to invigorate efforts to build a pipeline and generate the pool needed to draw future leaders from among women and other minorities. Efforts that have been promising include promoting the discipline and STEM subjects among female students in K-12, mentorship, summer programs or similar professional programs to promote veterinary medicine, and scholarships for women in general, and female minorities in particular.

Finally, I believe that targeted hiring of women into, and supporting women in the veterinary community to seek leadership positions in universities, state, and national executive boards, etc., would help to bridge the leadership gender gap that exists. The community still has some way to go to erase this gap and provide role models for more women to aspire to such leadership positions while maintaining a healthy balance between professional and personal lives. In the end, I cannot overestimate the value of cultivating and supporting female role models among the veterinary community.”

Dr. Colleen Hegg, associate professor

About: Colleen Hegg received her PhD in environmental toxicology from the University of Wisconsin in 1996 and has two adult children, ages 24 and 26. She is a neurotoxicologist and has studied lead neurotoxicity, HIV-1 AIDS dementia, and neuromodulation in the olfactory system. Since coming to Michigan State University, her research program has focused on how to restore neuronal function. She examines injury-evoked neuroregeneration and neurogenesis following exposure to environmental toxicants or cannabinoids.

Who is the woman who has influenced you the most over your lifetime? “I can think of a couple of women who have been extremely influential in helping me advance my scientific career. In high school, I had always liked math, and I wanted to become an accountant because that was what I thought you did if you had an interest in math. But a teacher encouraged me to go to a science exploration weekend for girls at Michigan State University. At that program, I saw women scientists running electron microscopes and working with a cyclotron. It planted the idea that as a girl I could be a scientist too. Representation matters. Having women role models throughout my education significantly changed my career path.

It was Mary Lucero, my post-doc mentor, who was instrumental in helping me become an independent scientist. In today’s world, having outstanding results and insightful and creative research proposals is not enough; one must also be able to articulate these ideas clearly and effectively. Mary was the first mentor that challenged me to face my fear of public speaking by providing thorough preparation and strategies to overcome my fear, and then plenty of opportunities to practice. She was a fierce advocate and one of my strongest champions, and I am thankful to have learned from such an excellent role model.”

How can the veterinary community be more supportive and inclusive of women? “One of the challenges in STEM and veterinary fields is retaining women in the profession. In academia, there is adequate representation of women at the level of resident, fellow, and assistant professor, but not in the higher ranks in academia or in leadership positions. The pandemic has highlighted a barrier that may prevent the advancement of women. The additional responsibilities as home caregivers had a greater impact on the productivity of women than on men as measured by publications and grant funding. There is no one-size fit all answer to this problem. Some personal recommendations include dispelling the myth of the perfect ‘super-parent’ who is effective and productive at work as well as 100% involved in all household activities, while at the same time maintaining a good work-life balance. It is impossible to meet this expectation. Institutional resources providing financial equity and support, flexibility in work schedule and promotion timelines, and high-quality mentorship could also help decrease attrition.”