History and Presentation

Peter, a 5-year-old Potbelly pig barrow, was presented to the MSU Large Animal Surgery Service in September of 2020 for acute respiratory distress due to a large laryngeal mass. The mass was identified via computed tomography (CT) at MSU one week earlier and appeared to originate from the left ventral aspect of the thyroid cartilage. A surgical plan was being made for removal but due to a deterioration in Peter’s condition with worsening upper airway noise and difficulty breathing, he was brought back in for a potential emergency tracheostomy.

On initial evaluation, Peter was bright, alert, and responsive but had notable inspiratory stridor and occasional coughing. Mucous membranes were pink and moist with a normal capillary refill time. Cardiopulmonary and gastrointestinal auscultation were within normal limits for a stressed pig in the hospital setting. The upper airway noise was particularly evident when he was excited or stressed.

Diagnosis

A week prior to the above admission, Peter was presented to the MSU Large Animal Internal Medicine Service for worsening respiratory issues characterized by a loud honking noise. A CT scan showed a soft tissue mass obscuring a large amount of the laryngeal lumen. The MSU Large Animal Internal Medicine Service recommended consultation with the MSU Large Animal Surgery Service to provide potential treatment options.

Treatment and Outcome

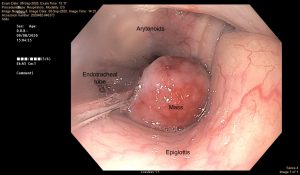

Shortly after admission, Peter was administered a parenteral antimicrobial (ceftiofur sodium) and anti-inflammatory medication (flunixin meglumine). He was then anesthetized, and a laryngoscope was used to place a small endotracheal tube past the laryngeal mass to administer oxygen and anesthetic gas. By securing the airway with the orotracheal tube, a tracheostomy was not necessary. The pedunculated mass was then successfully removed transendoscopically using a diathermic loop via the oral cavity and submitted for histopathology. Peter recovered uneventfully from general anesthesia and was placed in a stall for close monitoring.

Postoperatively, the upper airway noise was immediately resolved, and Peter was bright and comfortable, with a normal respiratory rate and effort. He was switched to oral medications (trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole, meloxicam, and omeprazole) in preparation for hospital discharge and remained comfortable with an excellent appetite. Histopathology of the laryngeal mass indicated a granuloma with no evidence of neoplasia.

Six months later, Peter returned to the MSU Large Animal Hospital for recheck endoscopy of the previously removed laryngeal granuloma. On laryngeal endoscopic examination under general anesthesia, there was no evidence of regrowth of the mass and the area had healed completely.

Peter’s owner reports that he is doing very well at home. His breathing issues are gone completely, and they could not be more ecstatic with the outcome.

Comments

Although laryngeal granulomas can be seen in horses with chronic arytenoid chondropathy, it has never been reported in a pig. Due to the specific anatomy of the swine species, the larynx is not a particularly accessible region.

In horses, we can remove laryngeal granulomas standing via transnasal endoscopy using light sedation and local anesthetic. In a pig, the snout prevents this approach, forcing us to access the larynx transorally or through a laryngotomy directly. Pigs also have an abundant amount of thick subcutaneous fat (jowls) along the ventral aspect of the lower jaw and neck, which makes a direct laryngotomy approach very risky.

We were lucky with Peter that we were able to remove the mass transendoscopically via the oral cavity and did not have to perform a direct laryngotomy. We also were extremely relieved that the anesthesia team was able to pass a small endotracheal tube past the mass. This avoided the need for a tracheostomy, which is similarly not an innocuous procedure in pigs due to the jowls. All in all, Peter’s case could not have gone better and a diagnosis of a granuloma with no evidence of neoplasia was just icing on the cake!