By Moriah Johnson, MSU Vetward Bound Enrichment Summer Program

Two summers ago, I was fortunate enough to be given the opportunity to travel to Thailand. I traveled through Bangkok and Chang Mai in the north, and the islands surrounding Phuket in the south. While I was in the north, two hours from Chang Mai, I worked and lived at an elephant sanctuary. Working with a wildlife veterinarian in the sanctuary opened up my world to the importance of veterinarians in the field of conservation. When it comes to conserving wildlife species, the health and the quality of life of the protected individuals is as important as the maintenance of the species as whole.

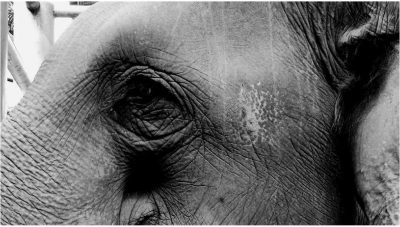

I worked with Asian elephants that had been rescued from lives of captivity. Some came from Bangkok where they were street beggars and circus objects. Others were rescued from illegal logging operations in the rain forests of southern Thailand. Most of my work involved helping with daily treatments for foot diseases, a major problem for captive elephants. Standing on concrete floors or packed dirt and poor husbandry practices leads to abscesses and other infections in their feet. Other elephants at the sanctuary suffered from old injuries, including untreated broken bones. The medical care they received at the sanctuary served as a reminder, to me and to them, of their past lives as commodities.

The process of rehabilitating these beautiful creatures was long and arduous. As the doctor worked on their medical problems, the on-site behaviorist treated their psychological traumas using positive reinforcement training. She worked hours a day with some and only a few minutes with others, depending on how long they tolerated it. As I observed the positive work done at the sanctuary, I knew that other captive elephants remained in violent and abusive situations. I saw this first hand when one night, a neighboring farm called our veterinarian to see about an elephant who was recumbent and unresponsive.

We all rushed two miles down the road to the farm. When we arrived, we saw a barely conscious and emaciated female elephant. The farmer, her owner, reported that she had been fine earlier that day but had since collapsed and was unable to stand back up. It was clear that the elephant’s low weight was chronic and it was unlikely that the onset of her symptoms had been sudden. However, the politics of conservation and the severity of her condition kept the doctor from berating the farmer. The doctor did what she could to keep the elephant comfortable, but she passed away in her sleep that night.

The next morning, I learned that she had tuberculosis. I also learned that tuberculosis is an epidemic in captive Asian elephants in Thailand. I was surprised to discover that TB was so pervasive and I was dismayed to learn the disease is zoonotic. This knowledge made me even more aware of the responsibilities and roles of the conservation veterinarian—to both non-human and human animals.

My many experiences in Thailand taught me that the life and work of a conservation veterinarian is indeed multifaceted. You are a veterinarian, diplomat, rehabilitator, and researcher all at the same time. It is a fast-paced, ever-evolving and humbling career. I left Thailand in a thoughtful state, wondering about my future responsibilities and hopeful contributions as a conservation veterinarian.