Quarter Horses are some of the most powerful of their species. Bred for bursts of speed, these horses have pronounced muscle development, and excel at competitive events and games as diverse as racing, reining, dressage, and rodeo.

So, when one third of a healthy Quarter Horse’s muscle wastes away in fewer than 48 hours, it begs the question, why?

Veterinarian and scientist Dr. Stephanie Valberg has answered this question in collaboration with Dr. Carrie Finno, associate professor and researcher at the University of California, Davis School of Veterinary Medicine. To make this discovery, Valberg, the Mary Anne McPhail Dressage Chair in Equine Sports Medicine and professor at the MSU College of Veterinary Medicine, first determined that with sudden muscle wasting, a horse’s white blood cells (lymphocytes) had begun to destroy muscle tissue. She named the disease immune-mediated myositis (IMM) because it appeared to be an autoimmune disease. Next, Valberg and Finno explored a potential underlying genetic basis for this condition. She and Finno found something remarkable—a mutation in a gene called MYH1, which is a gene that was not previously known to have any disease-causing mutations in any species.

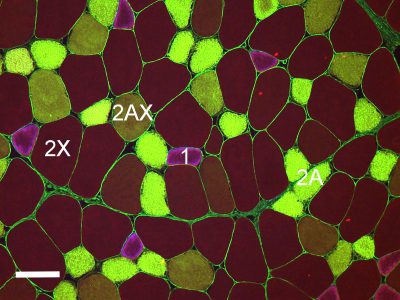

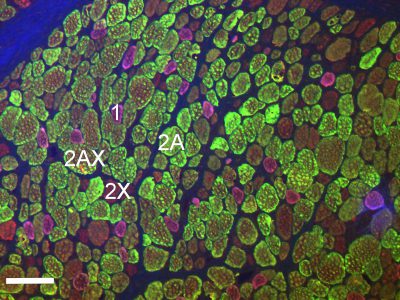

“The gene MYH1 produces the protein necessary for very fast speeds of contraction called type 2X myosin,” says Valberg. “More than 65 percent of the muscle cells in Quarter Horses contain type 2X myosin, which is what allows them to reach such high speeds. In Quarter Horses with IMM, we found that a mutation in the MYH1 gene altered the structure of the 2X protein, and somehow, this generated an autoimmune response, particularly if horses were exposed to Streptococcal infections.”

Valberg continues, “What is so unique about our finding is that autoimmune diseases are traditionally suspected to be due to mutations somewhere in the immune system. That’s not the case here; an abnormal immune response is arising because the mutation changes a contractile protein in muscle.”

It’s the first time that a mutation in skeletal muscle myosin has been linked to autoimmune disease. While horses with IMM can recover their muscle mass, they will often have a relapse of muscle wasting. Like many autoimmune disorders, relapses involve a genetic predisposition encountering the necessary environmental conditions—a perfect storm.

“We think wasting in IMM-susceptible Quarter Horses develops in one of two ways,” says Valberg. “Either they become infected with a Streptococcal bacteria that has a protein with similar amino acid sequence to that of the type 2X protein, which confuses the lymphocytes into attacking the bacteria and muscle cells; or, some sort of muscle damage occurs—maybe through an intramuscular injection like a vaccine—and in that process, the internal content of muscle cells gets exposed to the immune system, where the abnormal type 2X protein triggers an immune response to the muscle.”

To conduct their research, Valberg and Finno’s team worked with two large farms with existing cases of IMM, as well as many healthy horses. The researchers took DNA from all the horses—IMM positive and negative—and obtained muscle biopsies on horses exhibiting atrophy and that had lymphocytes in their muscles. Through genome mapping, whole genome sequencing, and genotyping, the scientists were able to identify a definitive link between the MYH1 mutation and susceptibility to IMM. The team found that 10 percent of Quarter Horses have the genetic mutation.

Valberg and her team also are working to commercialize a genetic screening test. This test will mean a muscle biopsy is no longer necessary to diagnose IMM—a hair sample will do—which will allow breeders to make informed decisions in their mating programs. The next step is to use this data to determine specifically what the mutation does and how it affects muscle function.

Variations of immune-mediated muscle diseases also manifest in dogs and humans. Dogs have unique, powerful jaw muscles to aid in chewing. These muscles have their own specific type of contractile protein type M myosin. Some dogs will develop an immune response to this myosin causing wasting of the jaw muscles called canine masticatory muscle myositis—truly a mouthful. Humans can develop a wide variety of immune-mediated inflammatory muscle diseases like polymyositis, which causes muscle weakness. The basis of these diseases is not yet known.

“Eventually, it will be interesting to see if the mutations in muscle genes like MYH1 also are responsible for autoimmune muscle diseases found in humans or dogs,” says Valberg. “It would open the door to a conversation about new therapies and preventatives.”

For more information regarding immune-mediated myositis, contact Dr. Stephanie Valberg or refer to the Equine Neuromuscular Diagnostic Laboratory.