Read More

Read More

Food fraud indelibly etched itself on the public consciousness in 2008 when 30,000 children in China were hospitalized with kidney problems because their milk powder was contaminated with melamine, an industrial chemical used in plastics, adhesives, countertops, and other materials. The scandal incinerated the reputation of China’s food system and victimized approximately 300,000 babies. In the United States, dogs and cats began dying suddenly, and the deaths were traced to melamine-contaminated food. In both cases, melamine was added to the food product to increase the protein content.

By Jamie DePolo

It seems recent, but food fraud has been going on for thousands of years,” says Dr. John Spink, assistant professor for the Department of Large Animal Clinical Sciences and director of the MSU Food Fraud Initiative. “There are records of tea fraud in 400 B.C.”

More recently, peanuts were used as an illegal filler in ground cumin, horsemeat was found in ground beef in the United Kingdom, and pomegranate juice was discovered to have been cut with grape juice. While some are concerned about being cheated by food fraud, food safety issues are the major concern for most people.

Befitting MSU’s land-grant tradition, the Food Fraud Initiative takes an interdisciplinary research, education, and outreach approach to tackling the issue, focusing on five main areas:

- The fraud itself, which is usually economically motivated and encompasses contamination and country of origin, ingredient, and production method fraud (a non-organic food being labeled as organic, for example). “While food fraud itself has been going on for centuries, as an academic discipline, it’s relatively new,” Spink says. “So, there are many disciplines involved, including public policy, criminal justice, food science, and veterinary medicine.”

- Business/enterprise risk management, a concept that Spink is helping food companies implement to evaluate potential fraud risks. “We help companies see where fraud might happen,” he says.

- General anti-counterfeiting strategies, which start by looking at the underlying drivers of the fraud opportunity. Once a company knows why and how someone might perpetuate fraud, it can create the most effective and efficient counter strategies. “There’s not a magic bullet here,” Spink explains. “Preventing fraud takes a systems approach.”

- Anti-counterfeit countermeasures, the academic term for the back-and-forth battle between the company and the people perpetuating the fraud. “These strategies are evolving and have to take into account how the people perpetuating the fraud will react,” Spink says. “Then, the strategies are modified based on that. It’s a chess match of wits.”

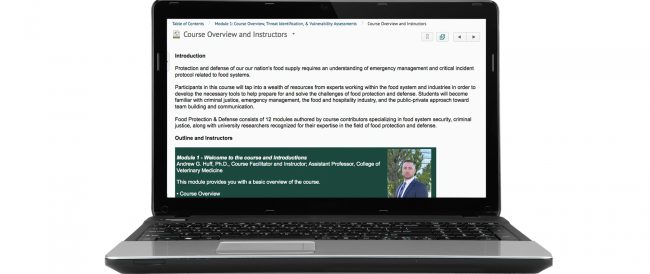

- Outreach, which includes massive open online courses (MOOCs) on various aspects of food fraud. Offered since 2013 in May and November, the MOOCs are free and open to anyone who would like to register, though there is a charge if a student wants a certificate of completion. “The MOOCs are open for a month,” Spink says, “and offer two weeks of content. The series includes a food fraud overview and a food fraud audit guide. About 200 to 600 students participate in each session and about 10,000 people from more than 50 countries have completed one or both courses.”