By Kathryn Winger, DVM, DACIM (Neurology)

History and Diagnosis

Louie, an 11-year-old neutered male mixed-breed dog, was presented to the MSU Emergency and Critical Care Medicine Service for evaluation of seizures. The owners reported that during the previous 24 hours, Louie had 5 generalized seizures, with the most recent occurring 1 hour prior to presentation. Immediately following each seizure, Louie was anxious and disoriented. The owners had otherwise not noted any behavioral changes at home.

Upon presentation, Louie was alert and responsive. His general physical examination was unremarkable. Given his recent history, a complete neurological examination with the MSU Neurology Service was performed. During cranial nerve assessment, it was discovered that Louie was blind in the left eye, as he had both an absent menace response and absent cotton ball tracking. A diagnosis of central blindness was made since his pupillary light reflexes were normal. The remainder of the examination— including gait assessment, proprioceptive positioning, myotatic reflexes, and palpation—was unremarkable.

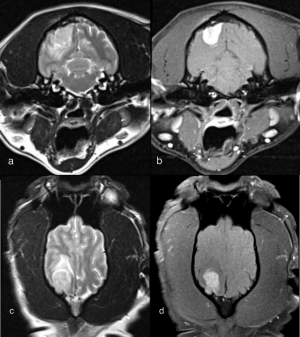

The history of seizures was supportive of a forebrain localization. While recent seizure activity can lead to altered behavior or mental state, general proprioceptive ataxia, delayed postural reactions, and blindness in the post-ictal period, these changes should always be symmetrical in nature. Louie’s central blindness affecting the left eye alone suggested a structural lesion in the contralateral thalamocortex, or right forebrain. Preliminary diagnostics—a complete blood count, serum chemistry, and thoracic radiographs—were unremarkable. To determine the underlying etiology of Louie’s clinical signs and develop an appropriate therapeutic plan, an MRI was warranted. Louie’s MRI revealed a T2 heterogeneously hyperintense and strongly contrast enhancing mass in the region of the right occipital lobe. The mass was well defined with distinct margins and adjacent pachymeningeal contrast enhancement. A moderate amount of T2-weighted hyperintensity was present within the adjacent cerebral white matter, consistent with perilesional edema (figure 1). The tumor’s extra-axial location, welldefined margins, uniform contrast enhancement, and dural tail sign were characteristic of a meningioma.

Treatment and Outcome

Due to the severity of his seizures at the time of presentation, Louie was admitted to the MSU Critical Care Unit for phenobarbital loading. This typically consists of a 4 mg/kg intravenous bolus every 4-to-6 hours for a total of 16 mg/kg. This was followed by administration of a maintenance phenobarbital dose of 2 mg/kg per os every 12 hours. Louie also was given an anti-inflammatory dose of corticosteroids to manage the perilesional edema identified on MRI. Over the course of the next two days, Louie remained seizure free and his vision returned. While palliative therapy can lead to a fair median survival time of 3–to-6 months, surgery was considered to be the most definitive way to treat Louie’s disease. Louie’s owners elected to proceed with surgery one month following initial diagnosis.

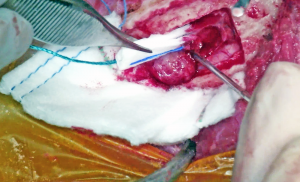

A standard rostrotentorial approach to the skull was performed. An incision was made in the skin and subcutaneous tissue over the sagittal crest. The thick temporalis fascia then was incised off midline and reflected to reveal the calvarium. Four pilot holes were made using a Hall air drill to outline the intended craniectomy site. These then were used to guide the drilling of an approximately four centimeters long by two centimeters wide bone defect. The edges were deepened to the level of the inner periosteum and a periosteal elevator was used to slowly remove the bone flap and visualize the mass underneath. Following durectomy, the mass was gently removed from the cranial vault, and the tumor cavity was debrided using a SONOPET ultrasonic aspirator. A porcine small intestinal submucosa graft was used as a substitute for the resected dura, and a piece of Gelfoam was placed in the defect prior to closure. The excised tissue was submitted for routine histopathology, and the diagnosis of meningioma was confirmed.

Louie was hospitalized for two days post-operatively, during which time he received analgesics, anti-epileptic drugs, anti-inflammatory corticosteroids, and intravenous fluid therapy. Continuous blood pressure monitoring and serial neurological examinations were essential to monitor for complications including hemorrhage, fluctuations in intracranial pressure, and brain herniation. Louie remained neurologically normal throughout his stay at the Hospital, and was doing well at the time of his three-week post-operative recheck. His corticosteroids were tapered over the course of six weeks. The phenobarbital will be continued long term. Three months following surgery, Louie remains clinically normal at home.

Comments

Meningiomas are the most common primary brain tumor found in dogs and cats. They are typically solitary tumors that arise from meningothelial cells. Meningiomas rarely exhibit aggressive or malignant behavior; therefore, extracranial metastases are uncommon. The most frequent presenting complaint in dogs is seizures, while in cats, lethargy and behavior change are reported more often. For canines and felines, median age at presentation is 10–12 years, and certain breeds of dogs including Golden Retrievers, Boxers, and Miniature Schnauzers are overrepresented.

While meningiomas are usually benign in both dogs and cats, differences do exist regarding their local behavior and disease-free interval. In contrast to well-encapsulated feline meningiomas, canine meningiomas tend to infiltrate the brain, making them more difficult to excise. Surgical resection alone for feline meningiomas can be curative for the lifetime of the patient. In dogs, standard surgical resection leads to a median survival time of 7 months. For this reason, adjunctive radiation therapy historically has been recommended, and can extend median survival time up to 30 months. More recent studies evaluating the intraoperative use of ultrasonic aspirators have demonstrated an augmented median survival time of 41 months. The ultrasonic aspirator permits more complete excision while reducing the risk of iatrogenic injury. In cases where surgical excision is not possible, radiation remains the mainstay of therapy. Recent advances in stereotactic radiotherapy offer the potential for long-term survival in patients with non-resectable tumors. This modality soon should be available to patients at the MSU Veterinary Medical Center.