When Stinger, a 10-month-old, intact male American Pitbull Terrier, was brought to an emergency clinic for what appeared to be bee stings, and then abandoned by his owner, it was up to Dr. Andrea Hasbach of the MSU Veterinary Medical Center had to solve this dermatitis mystery.

History and Diagnosis

Stinger, a 10-month-old, intact male American Pitbull Terrier that was up to date on vaccines, was brought to the Southwest Michigan Animal Emergency for severe skin irritation characterized by urticarial lesions over most of his body. The owner reported that Stinger had been stung by ground bees, and the skin lesions were thought to be secondary to the presumed bee stings. Unfortunately, after bringing Stinger to the emergency clinic, the owner abandoned him.

The emergency clinician prescribed Stinger cephalexin and prednisone. Initially, Stinger’s condition remained unchanged, but then his lesions worsened. The clinicians suspected the worsening may have been the result of an adverse drug reaction to the cephalexin. As neither medication appeared to be providing a clinical benefit, both drugs were discontinued.

As Stinger had been abandoned, an attempt was made to find a rescue agency. He was rescued by a local nonprofit agency called LuvnPupz and transferred to the Allegan Veterinary Clinic. Dr. JoAnna Kane oversaw his care, and determined a biopsy was needed to investigate the underlying cause of Stinger’s lesions and pruritus. A skin biopsy was collected and sent in for histopathology. Cytology revealed a bacterial infection, and the biopsy determined that sarcoptic mites were present. Stinger was treated with a single dose of Revolution, given a single oral dose of Bravecto®, and started on Apoquel®, as well as chloramphenicol. His skin began to improve, and within a few weeks was nearly normal. Given his improvement, he was neutered on October 17, 2016. Stinger was taken off all medications except the chloramphenicol for continued management of potential skin infections.

By October 22, Stinger’s skin lesions had returned and he had become markedly pruritic on his head, neck, and lateral trunk. By October 24, Stinger’s condition had deteriorated and his skin lesions were more severe than they previously had been with diffuse crusting over most of his body.

On October 28, a 2nd set of 4, 8mm punch biopsies and a fungal culture were collected and submitted for evaluation. In-house bloodwork revealed hypoproteinemia (characterized by hypoalbuminemia), a leukocytosis, and a mild anemia. Dr. Kane then referred Stinger to the MSU Veterinary Medical Center.

Upon presentation to Dr. Andrea Hasbach for physical exam, Stinger was quiet, alert, and responsive, although he was visibly depressed. His entire body was warm to the touch. Cardiopulmonary auscultation was within normal limits aside from a mild tachycardia. Mucous membranes were hyperemic with a capillary refill time of one second. Stinger’s mildly enlarged lymph nodes could be palpated in the submandibular area, and his abdomen was tense, but not painful. Stinger shivered throughout his exam and appeared markedly pruritic with any sort of manipulation.

Stinger’s dermatologic exam revealed erythematous pustules, papules, and crusts affecting the entire body, but more severely concentrated on his dorsum and proximal limbs. His distal extremities were less severely affected. Multiple large, moist, and exudative erythematous papulopustular lesions were coalescing into ulcerated plaques on the bridge of Stinger’s nose, the top of his head, the back of his neck, and on his lateral thorax. He also had severe crusting present along bilateral pinnal margins. The penis, prepuce, nasal planum, and oral, perianal, and periocular mucosa were unaffected. Stinger’s paw pads had occasional peripheral erythema, but were not ulcerated, thickened, or crusted.

Treatment and Outcome

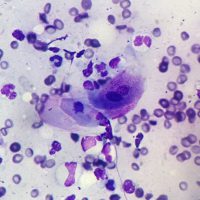

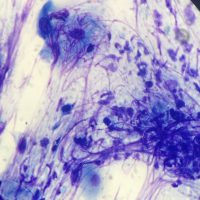

Dr. Hasbach performed superficial skin scrapings (negative), deep-skin scrapings (negative), and pinnal and dorsum cytology, which revealed neutrophils too numerous to count, moderated eosinophils, rare Malassezia, no bacteria, and occasional acantholytic keratinocytes. As biopsies of the current lesions had already been submitted a few days beforehand, additional biopsies were not collected. Stinger’s biopsy results showed that no parasitic or fungal organisms were detected, but histological examination revealed marked epidermal and follicular epithelial neutrophilic pustules (and crusts) containing acantholytic cells, and variable degrees of superficial perivascular dermatitis with epidermal hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis. These findings were consistent with a severe form of the autoimmune disease pemphigus foliaceus.

Pemphigus foliaceus is an autoimmune disease in which antibodies damage the cellular adhesion structures, called desmosomes, which exist between keratinocytes of the epidermis.

Given the severity of Stinger’s lesions and his deteriorating condition, Dr. Hasbach began his treatment by removing all non-essential medications and prescribing a high dose of oral prednisone (2 mg/kg PO q12h). To manage superficial bacteria without the use of oral antibiotics, use of daily dilute bleach (0.06%) soaks was recommended.

Stinger went to LuvnPupz with continued medical supervision by Dr. Kane while Dr. Hasbach consulted over the phone. For the first few days, Stinger’s condition did not worsen, but it did not improve, nor did he exhibit any of the typical side effects of steroids, such as increased appetite, thirst, or urination. Suspecting malabsorption in the gastrointestinal tract, Dr. Hasbach suggested a switch from oral prednisone to an equivalent dose of intravenous dexamethasone and an evaluation of his gastrointestinal function with assays for cobalamin (vitamin B12), folate, trypsin-like immunoreactivity, and pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity.

After the transition to the intravenous steroids, Stinger’s skin and demeanor started to improve. He was less pruritic and his ulcerative and crusted lesions began to dry up and heal. The gastrointestinal panel revealed low cobalamin, so Dr. Hasbach recommended 500 mcg of B12 supplementation weekly. After a week, clinicians would have the option to try transitioning Stinger to oral dexamethasone, and then plan on starting a secondary immunosuppressive medication before tapering down the oral steroids. Dr. Hasbach’s long-term immunosuppressive recommendations for Stinger included either cyclosporine-modified (5 mg/kg/day) or azathioprine (2 mg/kg per day initially and then reduced to every other day).

Now, Stinger’s lesions are nearly fully controlled, and he is undergoing the tapering process of oral dexamethasone. The long-term plan is to continue on oral azathioprine every other day.

Comments

Pemphigus foliaceus is the most common immune-mediated skin disease of dogs and cats. The primary cutaneous lesions associated with this condition are pustules, erosions, and crusts, and it can be variably pruritic. A high suspicion for the condition can be arrived at based on the clinical appearance of the patient; however, additional diagnostics are needed to rule out other disorders that can look similar. Initial diagnostics for any patient with pustules or crusts should include cytology, a deep skin scraping of affected sites, and evaluation of the patient for dermatophytosis with a Wood’s lamp and a fungal culture submitted to a diagnostic laboratory. Both demodicosis and pustular dermatophytosis can result in clinical lesions with striking similarity to pemphigus. Additionally, severe inflammation from bacterial infections and dermatophytosis can result in the presence of acantholytic keratinocytes on cytology. This makes biopsies necessary for a definitive diagnosis. Histopathology should reveal the presence of subcorneal to intraepithelial or follicular pustules containing inflammatory cells (neutrophils +/- eosinophils) and variable numbers of acantholytic keratinocytes.

In this case, the abandonment of the patient resulted in an uncertain initial history. It is unclear if Stinger actually was witnessed to be stung by ground bees, or if an insect sting was suspected with the initial skin eruptions. Further complicating arrival at an accurate diagnosis was the acute exacerbation of the patient’s signs with antibiotic and steroid treatment during his stay in the emergency hospital. Neither cephalexin, nor prednisone should have caused worsening of lesions associated with pemphigus foliaceus; thus, an adverse drug reaction must be considered. Removal of the cephalexin and prednisone did not result in resolution of his skin lesions, and a biopsy found sarcoptic mites, so it was initially believed that his pruritus was secondary to sarcoptic mange. However, urticarial and then papulopustular lesions with significant crusting are not typical of sarcoptic mange. Treatment of the mites corresponded with Stinger’s initial clinical improvement; however, his lesions reoccurred following his neuter. While it is unclear if this recurrence was the result of the physiologic stress of the neuter or simply part of the natural waxing and waning course that pemphigus foliaceus can take, it is clear that post-operatively, his lesions worsened significantly.

As with a large number of autoimmune disorders, there may be an underlying stimulus that triggers the development of the disease. Alternatively, no underlying trigger may ever be found. Some recognized triggers in humans and dogs include certain medications (cephalexin, trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole, etc.), use of multiple medications simultaneously, vaccines, and occasionally topical insecticides (Promeris®, etc.). Additionally, ultraviolet light is known to exacerbate lesions in some patients.

Treatment of pemphigus foliaceus typically requires lifelong management with immunosuppressive medications. There are no set treatment protocols, as medications and their doses need to be selected for each individual patient based on the severity of clinical signs and the medications’ efficacy and side effects. For small areas of focal lesions, topical glucocorticoids can be attempted. These topical options will sometimes work alone, but many patients will require use of systemic glucocorticoids, which provide a more rapid clinical response. A typical initial doses of prednisone in a dog may be 1 mg/kg orally twice daily, while prednisolone initially started at 1 to 2 mg/kg orally twice daily is used in cats. In cases of severe pemphigus, dermatologists may choose to use a much higher “induction” dose for several days, followed by lower doses until remission is achieved.

These high-dose pulse regimens have included oral prednisone at 10 mg/kg/day (or intravenous methylprednisolone succinate at 11 mg/kg/day) for three days, followed by lower oral prednisone (0.25 to 1 mg/kg orally every 12 hours).

Expected side effects of oral steroids should include polyuria, polydipsia, and polyphagia. With more chronic use, additional side effects will be noticed, such as loss of muscle mass, a pendulous abdomen, and thinning hair and skin, along with increased risks for gastric ulceration, liver injury, diabetes mellitus (dogs and cats), urinary tract infections, and calcinosis cutis.

Given these potential side effects and the fact that not all dogs will respond to a monotherapy with oral glucocorticoids, it is often advisable to start a second immunosuppressive medication that can be used long term. While there are several other immunosuppressive medications that can be considered for use adjunctively with steroids, perhaps two of the most commonly used medications include azathioprine (initially 2 to 2.5 mg/kg/day orally in dogs and then reduced to every other day) and cyclosporine-modified (5–10 mg/kg/day orally in dogs).

Cyclosporine-modified carries with it a more favorable side effect profile with reduced patient monitoring recommendations. It is more expensive and takes longer to work than azathioprine. Cyclosporine may take four-to-six weeks to have a clinical effect on pemphigus foliaceus lesions; thus, if used in concert with glucocorticoids, the glucocorticoids should not be tapered immediately after starting the cyclosporine. Cyclosporine’s side effects in dogs and cats most frequently includes a decreased appetite, vomiting, and soft stool or diarrhea, as well as less-frequently encountered hypertrichosis, gingival hyperplasia, papillomas, psoriasiform lichenoid-like dermatosis, and increased risk of disseminated systemic infections.

On the other hand, azathioprine is probably the most commonly used secondary medication to treat pemphigus foliaceus. Azathioprine is much less expensive than cyclosporine-modified, making it an attractive choice for many clinicians and owners. Side effects can include bone marrow suppression with potential for pancytopenia, vomiting, diarrhea, liver toxicity, and acute pancreatitis. Therefore, patient monitoring with CBC and serum chemistry at baseline and every two-to-three weeks for several months until stable is recommended. As both azathioprine and glucocorticoids can result in elevated liver enzymes (hepatotoxicity and vacuolar hepatopathy, respectively), their use concurrently can make it difficult to interpret elevated liver values in serum chemistry. In our experience, the glucocorticoids must be tapered and discontinued to assess if liver injury secondary to azathioprine is occurring. Once blood values are stable, continued monitoring of the CBC and serum chemistry should take place every three-to-four months.

Ultimately, the goal of therapy is to be able to taper down steroids to the lowest dose necessary (when used as a monotherapy), or to be able to discontinue use of glucocorticoids (when used in conjunction with another immunosuppressive medication). When azathioprine is used, the author will typically start with 1.5–2 mg/kg azathioprine orally once daily and 1 mg/kg prednisone twice daily in dogs. Once remission is achieved clinically, the prednisone is tapered by no more than 15–25% at 2–3 week intervals until steroid-induced side effects are minimized, after which the azathioprine frequency will be reduced to every other day. As mentioned, this process is tailored for each individual patient. Once the azathioprine is at the maintenance dose of every other day and bone marrow and liver values are stable, the laboratory monitoring can be reduced to every 3–4 months as indicated.

A variety of other medications have been used in the control of pemphigus foliaceus, such as mycophenolate mofetil, cyclophosphamide, intravenous immunoglobulins, and dapsone. However, in the event of treatment failures with the medications discussed herein, it would be advisable to have the patient referred to a veterinary dermatologist before attempting to use these therapeutics.