By Susannah Haupt

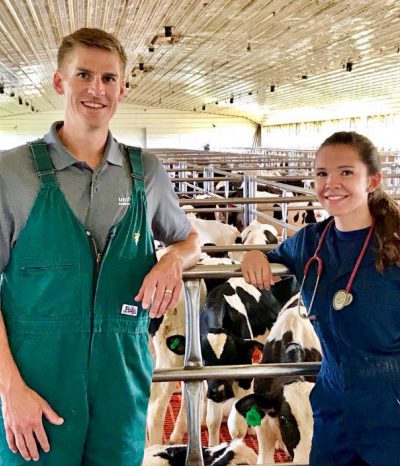

This summer, I had the pleasure of working in conjunction with Midwest Veal, headquartered in Indiana, and Pharmacosmos, headquartered in Denmark, to immerse myself in the role of the veterinarian in the veal industry and conduct iron trials on veal calves. I worked closely with Dr. Marissa Hake, Midwest Veal’s first full-time veterinarian, to visit veal barns and aid in veterinary procedures. I also worked closely with Dr. Chris Olsen, the veterinarian for Pharmacosmos, to run the iron trials.

Where exactly does veal come from? Since dairy farms are comprised almost entirely of milk-producing females, most male calves born are sold for beef or sold into the veal industry. The veal calves can be used either as bob veal, which are sent to harvest within days and weigh around 80 pounds, or as milk-fed veal, which are raised for 6 months and weigh around 500 pounds at harvest. By weight, 75 percent of all veal raised in the United States is milk-fed veal. Midwest Veal, along with all other members of the American Veal Association, only raise milk-fed veal. While the consumption of veal in the United States has been decreasing since 1944, veal provides a healthy meat choice, as a 3-ounce serving has only 166 calories and provides 29 percent of the recommended daily intake of zinc, 36 percent of the daily intake of niacin, and 23 percent of the recommended vitamin B-12 intake.

What makes veal different? Even though veal is considered a red meat, the characteristic presentation is a softer meat and paler color due to competition with the beef industry for consumers. Veal farmers are docked points and lose money at harvest if the veal carcass is too red, so there is pressure on the veal industry to produce paler meat. This paler meat does not come without complications, though. To produce the paler meat, these milk-fed calves need a low, controlled concentration of iron. A big part of my work with Pharmacosmos was to run trials to help determine the optimum amount of iron a calf should receive to produce a paler meat, but not result in anemia. The goal of the veal industry is not to produce anemic calves because anemic calves firstly, present an animal welfare concern due to sickness, and secondly, do not grow as well and therefore, result in less money in the farmers’ pocket.

What is the role of the veterinarian? There is an increasing demand for veterinarians outside of the traditional role of private practice as consumers are demanding better meat quality and better animal welfare standards. Where veal was traditionally thought of as being raised tethered to small boxes and completely in the dark, veal now is raised in group housing with natural lighting. The hiring of a staff veterinarian proves that the company is committed to raising healthy calves. In addition, part of my role this summer was to assist Dr. Hake with various veterinary procedures, such as putting on splints and casts, giving iron injections to all calves whose blood tested low in iron, and conducting audits for every veal barn to ensure compliance with new welfare standards. This internship opened my eyes to the importance of veterinarians in ensuring a safe meat supply and animal health. Overall, the role of the veterinarian is expanding to help create a better world for both people and animals.