Watch these goats in action here.

Two surgical procedures that are normally reserved for small animals were conducted on goats at the MSU Veterinary Medical Center this year:

- The first, a tibial-plateau-leveling osteotomy (TPLO) to repair a complete cruciate ligament tear;

- The other, use of an I-Loc interlocking nail to repair a complicated fracture of the proximal femur.

These unique cases presented excellent learning opportunities within a veterinary teaching hospital—when many veterinary students train primarily to treat small animals, the brain-stretching opportunity to apply familiar knowledge to a large animal context is invaluable.

“These cases demonstrated that small animal and orthopedic knowledge can be applied to large animals,” explains Dr. Ashley VanderBroek, assistant professor of large animal surgery. “And as goats gain popularity as companion animals, we as veterinarians need to be able to adapt to provide the same medical advances for them as we do other companion animal species, like dogs and cats.”

Elsa: First Reported TPLO in a Goat

This story features senior surgeons Dr. Loïc Déjardin, Dr. Ashley VanderBroek, and Dr. Maria Podsiedlik; residents Dr. Lindsay Monroe, Dr. Rachel Hilliard and Dr. Kelly Schrock; and assistant Katie Bederka (DVM Class of 2024).

Elsa, a three-year-old Nigerian Dwarf doe, had undergone a mid-femoral amputation of her left hind limb as a kid, but in adulthood had no difficulties ambulating—until late 2023, when Elsa exhibited acute right hindlimb lameness and was only able to stand for short periods of time. Based on physical examination and presence of a cranial drawer sign, her primary veterinarian suspected a complete rupture of the cranial cruciate ligament.

She was referred to the MSU Veterinary Medical Center in early January to discuss the logistics of performing a tibial plateau leveling osteotomy (TPLO). This is a well-described surgical procedure to restore normal limb function in dogs with cruciate ligament tears, but it had never been reported in a goat.

“Unlike in people and in dogs, cruciate injuries are not common in goats,” says VanderBroek. “If Elsa were a dog, we’d have known what to expect in terms of recovery and prognosis, but we had nothing to go on.”

After examination and confirming a cranial cruciate ligament rupture, Elsa’s surgical team began planning the approach to the procedure. Abscesses associated with her prior amputation site were treated to remove potential sources for infection, but the lack of an additional hindlimb left her post-surgery quality of life an unanswered question.

“After surgery, she had to be able to stand and use that limb to move around as large animals can’t really be bed-rested,” says VanderBroek. “Immediately following surgery, dogs are typically non-weight bearing on the operated limb. By the time they leave the hospital, they should be partially weight bearing, but it can take a couple weeks for them to bear full weight on the operated limb. Elsa didn’t have that luxury because her other hind limb had been previously amputated. Additionally, because goats don’t live in the house, there was an increased risk of infection and incisional complications. This all involved a lot of honest conversations with the family, and careful planning as we considered these unknowns.”

The unfortunate timing of an abscess at her previous amputation time, necessitated that her surgery be postponed until March of 2024. VanderBroek partnered with Dr. Loïc Déjardin, W. O. Brinker Endowed Chair of Veterinary Surgery. The two combined their expertise in large animal surgery and small animal orthopedic surgery to perform the procedure.

Elsa's Surgery

Because Elsa is a ruminant and has four compartments to her forestomach, she had to be fasted for a much longer period of time than a dog or human would prior to undergoing general anesthesia. Despite extended fasting, ruminants still frequently regurgitate and produce copious amounts of saliva under anesthesia requiring the airway to be protected via endotracheal intubation swiftly following induction.

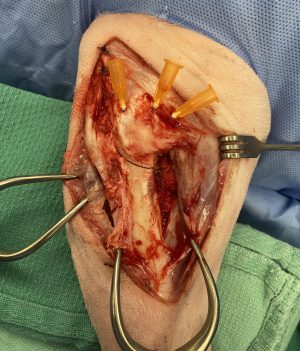

Following routine preparation and draping, a craniomedial parapatellar approach was used to access the stifle. An arthrotomy was performed to assess the joint surface and soft tissue structures, which revealed a non-functional cranial cruciate ligament. However, the medial meniscus and articular cartilage appeared within normal limits. Viewing the joint from an arthrotomy was a unique perspective for the large animal residents as joint surgery in horses is almost exclusively performed via arthroscopy.

After lavaging the joint, the capsule was closed and hypodermic needles were placed along the tibial plateau to aid in TPLO plate positioning. This was particularly critical as the shape of the proximal femur in a goat differs slightly from a dog, so the margins of the bone needed to be precisely visualized. Based on previous radiographic measurements, a 21-mm saw blade was used to create a curved osteotomy of the proximal tibia—the cut began at the cranial aspect of the tibial plateau, just caudal to the patellar ligament, and curved distocaudally, exiting from the caudal aspect of the proximal tibial metaphysis.

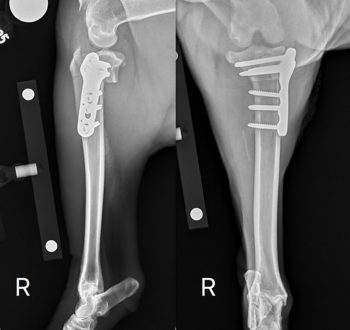

Based on the previously measured preoperative tibial plateau angle of 21 degrees, the osteotomy was rotated 5.8 mm to establish a new tibial plateau angle of approximately 5 degrees. This alignment was fixed by placement of a 3.5-mm TPLO plate and secured with two cortical screws and four locking screws. Closure was routine and postoperative radiographs showed appropriate placement of the implants.

Elsa recovered from anesthesia without complications and was able to rise and move around her stall on her own that evening.

She used the limb reluctantly due to pain but this gradually improved by the time of hospital discharge two days later. In the coming weeks, Elsa’s comfort level was reported to be significantly improved and her incision healed well. At her two-month postoperative visit, the osteotomy site appeared fully healed radiographically, and there was no swelling or pain upon palpation of the stifle. Elsa demonstrated no difficulty ambulating and could fully weight-bear on the affected limb.

“Although this is the first time that a TPLO has been performed in a goat, I would definitely consider it for future cases since Elsa has recovered so well,” says VanderBroek.

Kora: I-Loc Implant Saves a Leg

This story features senior surgeons Dr. Loïc Déjardin, Dr. Ashley VanderBroek; Residents Dr. Lindsay Monroe and Dr. Rachel Hilliard; Assistants Erica Walker and Cory Howard (DVM Class of 2024).

Kora, an eight-year-old Angora x LaMancha doe, was presented to the MSU Veterinary Medical Center in February 2024 for acute left hind limb lameness. She was able to ambulate on her other three limbs without difficulty but had been completely non-weight bearing since the lameness was initially noted.

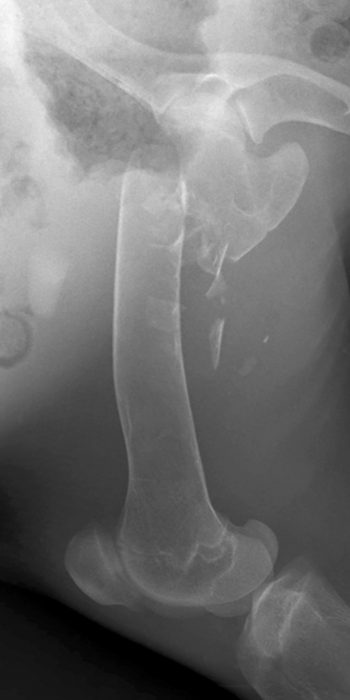

On physical examination, there was severe instability of the left hind limb with crepitus noted upon palpation of the proximal femur, consistent with a fracture. Radiographs confirmed this assessment revealing a closed, displaced, comminuted, transverse fracture of the proximal left femur.

“In large animals, we usually repair long bone fractures with plates and screws,” explains VanderBroek about the approach to Kora’s injury. “But because the fracture was so proximal (near the hip joint), there was not enough bone for the screws and plate to obtain adequate purchase and create a secure construct.”

She approached Déjardin, who helped her identify that the fracture configuration was suited for the I-Loc interlocking nail—avoiding amputation as an alternative option. Déjardin is the designer of the implant, which is most commonly used in dogs and cats but has been used to repair tibial fractures in calves on at least two occasions.

Kora's Surgery

Kora was placed under general anesthesia and positioned in right lateral recumbency. After routine aseptic preparation, a lateral approach was made to access the femur. The fracture site was examined and the corticocancellous comminution and fracture hematoma was preserved for grafting.

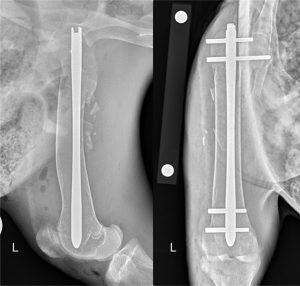

Based on preoperative computed tomography (CT) to further characterize the fracture and aid in surgical planning, a 7-mm x 147-mm I-Loc interlocking nail was selected. An awl was inserted into the trochanteric fossa to create a bone tunnel, and the fracture was reduced and stabilized by normograde placement of the nail through the proximal fragment into the distal fragment. The implant spanned the length of the femur, taking care not to violate the articular surface of the stifle. To optimize the length of the bolts anchored in the femoral head and neck, the aiming device was rotated until the plane of the locking bolts was oriented lateral to medial, maximizing purchase.

Following preparation of the bolt holes, a measuring device was used to determine the appropriate bolt lengths. After cutting the bolts to size, they were inserted in sequence from proximal to distal with two bolts placed in the femoral head and neck, and two bolts placed in the distal femoral metaphysis.

Once the implants were in place and the construct was secured, the fracture hematoma with corticocancellous comminution was replaced at the fracture site and the surgical site was routinely closed. Postoperative radiographs showed appropriate placement of the implants with good alignment of the bone and Kora recovered uneventfully from general anesthesia.

By the following morning, Kora was already bearing some weight on the operated limb. Her recovery process continued at home and at her recheck appointment three weeks later, she was fully weight-bearing on the limb, with early callus formation present on radiographs. Subsequent recheck examinations showed continued improvement, and at the most recent visit in June 2024, Kora had full range of motion of the left hind limb with radiographs showing complete radiographic union and a circumferential bridging callous along the shaft of the femur.

The I-Loc interlocking nail—more commonly used in small animals—was first placed in a production animal species in 2018, when a Holstein calf named Lulu presented to MSU upon suffering a tibial fracture during birth.