By Peter Fowler, DVM Class of 2020

Earlier this year, I had the opportunity to travel to Nepal as part of a public health clerkship through the MSU College of Veterinary Medicine. I went to study the prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of Salmonella enterica, one of the world's most important zoonotic pathogens.

Poultry is one of Salmonella's vectors of choice; here, it can easily contaminate meat and eggs. S. enterica contamination leads to an estimated 93 million cases of gastroenteritis globally each year, which results in an estimated 155,000 deaths, with higher morbidity and mortality rates in developing countries like Nepal. But that number could be a lot higher due to underreporting and lack of surveillance in specific countries, particularly in South Asia. Also of grave concern is the widespread and unregulated use of antibiotics within the poultry industry in many of these countries. This has led to strains of salmonella that exhibit multidrug resistance (MDR), which makes management and treatment of salmonellosis increasingly complicated.

This project originated with a proposal sent to Michigan State University by a Nepali nonprofit organization that the College has built a relationship with over the past three years, the National Zoonoses and Food Hygiene Research Center in Kathmandu. The hope was to build some baseline surveillance data on S. enterica. In addition, we aimed for the data to serve as a guide for future projects in human medicine that seek to identify possible sources for MDR salmonella linked to gastroenteritis among Nepal’s general population. Most of the previous research in Nepal has focused on the prevalence of S. enterica at the market level. Many of these studies lack data on farm practices and distribution practices that might give some clues as to the source of this contamination.

For this project, we combined farm-level environmental sampling, along with a farm practice survey, to better understand what practices might help lower the prevalence of Salmonella that enters the market. We also collected biological samples from nearby slaughterhouses. In total, we visited 18 farms and 20 slaughterhouses and collected a total of 705 samples.

Upon arrival in Kathmandu, I met with Minu Sharma from the National Zoonoses and Food Hygiene Research Center and Dr. Subir Singh from Forestry and Agriculture University in Rampur (AFU) to discuss the project details. During the first week, we field tested and finalized the survey design and sample collection protocols. After we purchased supplies at a local distributor, I flew from Kathmandu to Bharatpur. Once there, I met Dr. Sumit Sharma Poudel, a recent graduate of the AFU Veterinary Medicine Program. After I tried (awkwardly) to balance my bags on the back of his motorcycle, we set off to Rampur to the University where we would be based.

We spent the next two weeks riding Sumit’s motorcycle around the beautiful Nepali countryside in the intense heat and collecting samples from farms and slaughterhouses. The mornings started at 5:00 a.m., as we needed to get materials ready for sample collection. In the middle of the day, when the heat was too much, we would take a break for lunch: dal bhat (lentils and rice, a traditional Nepali dish) and fresh crushed cane juice.

After we got the samples back to the lab at AFU, we spent the evenings preparing and sterilizing pre-enrichment media. All our samples needed to be pre-enriched in buffered peptone water to help foster any S. enterica that might be present. After being pre-enriched for 24 hours, our subsamples were packaged in a cooler and prepped for delivery to Kathmandu. Power outages were our main obstacle here, as they frequently left us unable to sterilize materials. We often had to clean glassware by flashlight until the wee hours of the morning.

One of the things that struck me about the farms we visited was how familiar they were with biosecurity. Most of the farms were contracted by feed companies and hatcheries to raise the chicks. They would receive the day-old chicks and would raise them until they were old enough to slaughter, at which point the contractor would pick up the live chickens and distribute them to markets or antemortem houses.

Nearly all farms practiced an all-in/all-out system, in which all the chicks arrived at once and left at once. Their facilities were then left vacant and disinfected with a variety of chemicals followed by incineration. Many facilities would remain vacant for one to two months before they introduced a new round of chickens.

Chickens picked up by the distributors from the farms would be delivered to markets alive. As needed, the chickens would be slaughtered. Immediately after slaughter, chickens are boiled for several minutes in order to facilitate defeathering. This practice of boiling to loosen the feathers actually serves a good double purpose—that may not have been intended—of reducing contamination and bacterial load on the chicken. They are then put in a drum machine that tumbles them around and removes the feathers. After this, the GI tract is removed and the chicken is placed in a deep freezer. This was a fairly common practice in many of the meat markets, but some that lacked access to refrigeration would leave the chicken out on the counter with a screen box or cloth covering it to keep flies away.

One of the main concerns going into this project was the unregulated use of antibiotics that created a resistance among Salmonella strains in the area. With only 1,200 veterinarians in the whole country, and only a small fraction of that number who work with poultry, many of the poultry farmers have to make use of paravets in order to get advice on keeping their flock healthy.

A paravet degree is an 18-month technical program, compared to the 4-year medical program that veterinarians are required to complete. While paravets fill a crucial role in the poultry industry, there is less focus on proper antibiotic stewardship due to the accelerated nature of their program. It was fairly common in our survey to find antibiotics indiscriminately used prophylactically and for growth promotion.

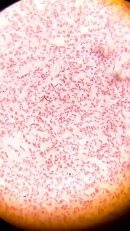

After sample collection was complete, I caught a public bus back to Kathmandu to assist with sample processing. Back at the National Zoonoses and Food Hygiene Research Center, I worked with biochemists, Dahn Pant and Yogendra Shah, to isolate and test for Salmonella through selective culture and biochemical testing. This was the most tedious part of the project.

One obstacle was the difficulty of obtaining a positive control sample, as only one facility in the country maintains live Salmonella cultures, and the one they had was not viable. We also had trouble with contamination, as the repetition of several biochemical tests on the same sample yielded different results. This suggested that colonies were not being adequately isolated and purified. We paused during my last few days in Kathmandu to revise and refine our protocols to ensure our results were reliable. Unfortunately, I had to leave before we could get final results, but Dahn and Yogendra are currently working through the samples with the help of the lab assistant Kabita Shahi and should be sending us results soon.

Since Sumit and Subir have a focus on working with the poultry industry in Nepal, Sumit will be writing up the project. We expect the results to help lay the groundwork for future Salmonella surveillance and to help inform regional farm management practices.

Nepal is an amazing country and I’m extremely lucky to have had the opportunity to learn from all the wonderful people I met along the way. I want to thank Dr. Melinda Wilkins for giving me the opportunity to contribute to these important collaborations. I also want to thank Kabita for showing me around Kathmandu and introducing me to all the amazing street food. To Meena and Dahal, thank you for teaching me how to make some delicious Nepali dishes. I’m looking forward to future trips and collaborations.

International Field Study: Prevalence and Antimicrobial Resistance of Salmonella enterica in Nepal

Salmonella enterica is widely regarded as one of the most important zoonotic foodborne pathogens globally. One important source for this pathogen is poultry, where it commonly contaminates meat and egg products (1). S. enterica contamination leads to an estimated 93 million cases of gastroenteritis globally each year, which results in an estimated 155,000 deaths, with higher morbidity and mortality rates in developing countries (2). Underreporting of cases and lack of surveillance data in many countries, particularly in South Asia, suggests that these numbers may be much higher (3). Additionally, the widespread and unregulated use of antibiotics within the poultry industry in many of these countries has led to strains of salmonella exhibiting multidrug resistance (MDR), which makes management and treatment of salmonellosis increasingly complicated (4). This cross-sectional study seeks to provide baseline data on the prevalence of MDR Salmonella spp. among the farms and slaughterhouses in Nepal’s leading poultry producing district, Chitwan, and possible practices in farm management, which may lead to further spread. A total of 695 samples (255 environmental samples from 17 poultry farms and 440 biological samples from 20 slaughter houses from across the Chitwan district) will be taken at random during the month of May and selectively cultured for Salmonella. Isolates will then be tested for antimicrobial resistance against 12 commonly used antibiotics of importance to both animal and human medicine regionally. Participating facilities will be given surveys to help assess any correlation between certain farm practices or locations and the prevalence of Salmonella-positive samples. Descriptive statistics will be used to establish baseline data on prevalence across the region, and if there is sufficient sample size among isolates, regression analysis will be used to determine possible correlations with farm management practices. The results of this project will be seminal in informing improved farm management practices and public health policies in Nepal. This also will serve as important baseline-data for future projects in human medicine that seek to identify possible sources for MDR Salmonella linked-gastroenteritis among the Nepal’s general population.

References:

- H. Jin Cheong et al., Characteristics of Non-typhoidal Salmonella Isolates from Human and Broiler-chickens in Southwestern Seoul, Korea. (2007), vol. 22, pp. 773-778.

- 2. S. Majowicz et al., The Global Burden of Nontyphoidal Salmonella Gastroenteritis. (2010), vol. 50, pp. 882-889.

- 3. FAO, "Poultry Sector Nepal. FAO Animal Production and Health Livestock Country Reviews," (2014).

- 4. P. L. Winokur et al., Animal and Human Multidrug-Resistant, Cephalosporin-Resistant Salmonella Isolates Expressing a Plasmid-Mediated CMY-2 AmpC β-Lactamase