Lou Newman’s photography is an extension of a lifetime spent paying attention. A veterinarian and veterinary pathologist who earned his PhD at Michigan State University in 1978, Newman built a career rooted in observation, problem-solving, and animal care. In addition to doing his doctoral research at MSU, Newman served as an instructor in Large Animal Clinical Sciences and led the College’s Veterinary Extension Program. It was here at Michigan State that Newman came to rely on photography—a hobby he’d always enjoyed—as an essential tool in teaching.

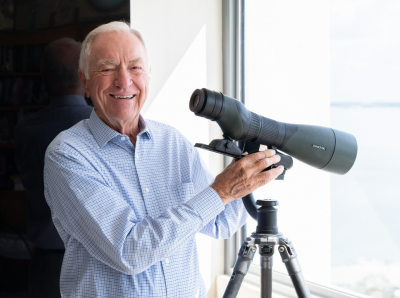

After he retired from veterinary medicine, Newman turned more fully to photography. Though he briefly explored this work as a business, he ultimately found the greatest satisfaction in the act of observing and capturing wildlife itself—using his retirement years to travel, refine his craft, and continue doing what he had always done best: paying close attention to the world around him.

Now 95 years old, Newman has been to every state, 72 countries, and all 7 continents. Settled in Sarasota, he still spends a large portion of his days behind the lens.

Check out some of Newman's photos below and see more on his online portfolio.