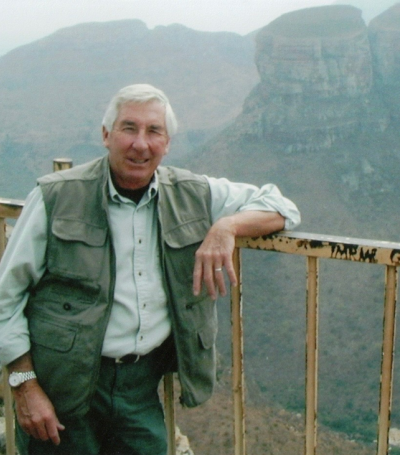

When John R. Welser arrived at the Michigan State University College of Veterinary Medicine in 1975, it was clear from the start that he was a different kind of leader. “I was on the search committee for dean,” says Dr. Ed Robinson, who was then a faculty member jointly appointed in Physiology and Large Animal Clinical Sciences. “We brought in all these people who were very stiff and academic. But then, here comes this charming guy from Georgia, an MSU alum, who talked about all the possibilities that he saw for the College. Talk about a breath of fresh air!”

A proud Spartan, Welser earned his DVM from MSU in 1961 before completing his PhD at Purdue University. His return to his alma mater marked the beginning of eight years of leadership that reshaped and strengthened the College. More than four decades later, Welser’s impact still echoes through the College’s curriculum, diagnostic capabilities, and culture of collaboration.

The Creation of the Diagnostic Laboratory

Welser’s sense of possibility was put to the test quickly after he took the helm. Not long after he arrived at MSU, Michigan’s agricultural community was shaken by one of the most serious crises it had ever faced: the contamination of livestock feed with polybrominated biphenyl (PBB), a fire-retardant chemical. Farmers across the state were losing cattle, and concerns about human health were mounting.

Welser acted quickly. Working closely with Dr. Kenneth Keahey in the Department of Veterinary Pathology, he helped lead an effort to expand the College’s diagnostic capabilities, recognizing that protecting animal health also meant safeguarding the people and communities who depended on it. Together, they developed a proposal for what would become the Animal Health Diagnostic Laboratory (today the College’s Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory), sharing their vision directly with state legislators. Their proposal resulted in an investment of $300,000 in annual funding over three consecutive years—support that laid the foundation for a laboratory that has since grown into a world-class facility.

“He was the driving force behind the Diagnostic Lab, and he built the conditions that allowed it to grow,” says Robinson. “It was essential for the PBB outbreak, and then again later when there was a bovine tuberculosis outbreak in deer.”

Those incidents were only the beginning of a pattern. Today, when Michigan faces a threat to animal health, such as recent ongoing outbreaks of highly pathogenic avian influenza, the Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory that Welser helped establish is called upon to respond. The scale and sophistication with which the Lab now operates reflects the belief that Welser held decades ago: that veterinary diagnostics play an essential role in protecting animal and human health.

Championing Clinical Specialties

Welser was a passionate supporter of clinical specialties within veterinary medicine, as the 1960s and ‘70s saw the formation of some of the earliest professional organizations governing the training and certification of veterinary specialists. Recognizing that students and faculty alike would benefit from deeper expertise, he supported the development of specialized areas such as orthopedic surgery, internal medicine, ophthalmology, radiology, and cardiology. By identifying outstanding clinical educators, providing them with the resources to grow their programs, and creating opportunities for students to engage with advanced training, Welser helped transform MSU into a place where specialization was intentionally cultivated.

“Welser’s vision enriched the professional training of countless veterinarians, and it set the stage for Michigan State to become a model for specialty veterinary education nationwide,” recalls Dr. George Eyster, a faculty member at the time who specialized in cardiology.

The MSU Veterinary Medical Center is currently home to more than 15 specialty services, all staffed by board-certified experts who train the next generation of veterinary professionals. By anticipating the growing need for clinical expertise and investing in specialty education decades ago, Welser positioned MSU to lead in both advanced patient care and professional training.

A Return to the Four-Year Curriculum

As dean, Welser came to recognize the limits that the existing three-year professional program imposed on both student learning and faculty opportunities for research. He led a transition back to a four-year curriculum, a change that was implemented in 1979. This additional year allowed students more time to work directly with patients, engage deeply with clinical specialties, and develop the analytical skills necessary for advanced practice. Faculty, in turn, gained greater flexibility to balance teaching with research and service.

“Within the new curriculum, Welser was instrumental in implementing a new approach whereby students spent almost all of their final year in clinics, not in the classroom,” says Dr. Janver Krehbiel, who was then the director of the Clinical Pathology Laboratory. “This gave students the chance to be in the Hospital, gaining clinical experience.” That hands-on approach continues to define veterinary education at MSU today.

Charm and Charisma

Welser’s impact extends far beyond policies and programs; his charisma and genuine interest in people left a lasting mark on students, faculty, and colleagues alike. Known for his charm and good nature, Welser often walked through clinics, laboratories, and classrooms, stopping to ask, “What’s new?”

“He showed a real interest in clinic activities and would often just walk through and show support. Everyone really appreciated that,” says Dr. Jim Sikarskie, another faculty member during Welser’s tenure.

Eyster adds, “His relationship with the students was excellent, and I didn’t know a faculty member that didn’t like him.”

Beyond the College, Welser’s skill in relationship-building proved invaluable. He forged strong connections with state legislators, creating a network of support that facilitated funding for the College’s programs and facilities.

“He once said to me that he’s eaten more chicken dinners with politicians than he ever thought he would,” recalls Eyster. “But he knew the right people to go after to chase his vision.”

A Family Legacy

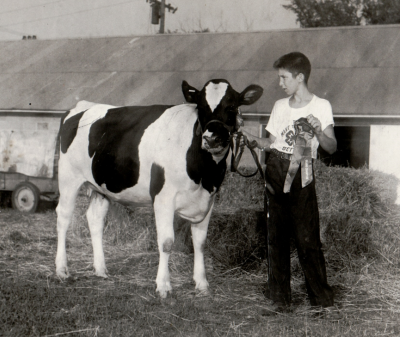

One of the most enduring reflections of Welser’s passion for veterinary medicine is that it inspired his daughter Jennifer to follow in his footsteps, graduating from the MSU College of Veterinary Medicine in 1996. Jennifer recalls being drawn to the profession long before she fully understood what her father did. As a child, she often accompanied him to the College on weekends and for events, gaining what she describes as a “behind-the-scenes glimpse” of his world. More influential than those early visits, however, was witnessing how deeply he loved his work. “The biggest, almost unspoken, influence he had on my choosing this profession was seeing how much he enjoyed every minute of it,” she reflects. “He always took advantage of the opportunities provided, created his own opportunities, and put people first.”

Welser’s curiosity and energy carried into every aspect of his life. Known within his family for his boundless enthusiasm and creative problem-solving, he was a constant learner who never shied away from a challenge “unless he pulled out one of his famous dad responses, ‘let’s not and say we did!’” says Jennifer.

According to his wife Kathryn, Welser’s passion for veterinary medicine was inseparable from the way he lived his life. At home, he often spoke with enthusiasm about the students, the research, and the joy he found in working alongside colleagues across campus. Above all, she recalls, he was deeply devoted to his family and immensely proud of his children—both Jennifer and their son, Jeff. “His charisma made him fun and unique to everyone who was lucky enough to know him,” says Kathryn.

That Dean Welser spirit, evident both at home and at the College, lives on through the people, programs, and purpose that were shaped by his extraordinary leadership.